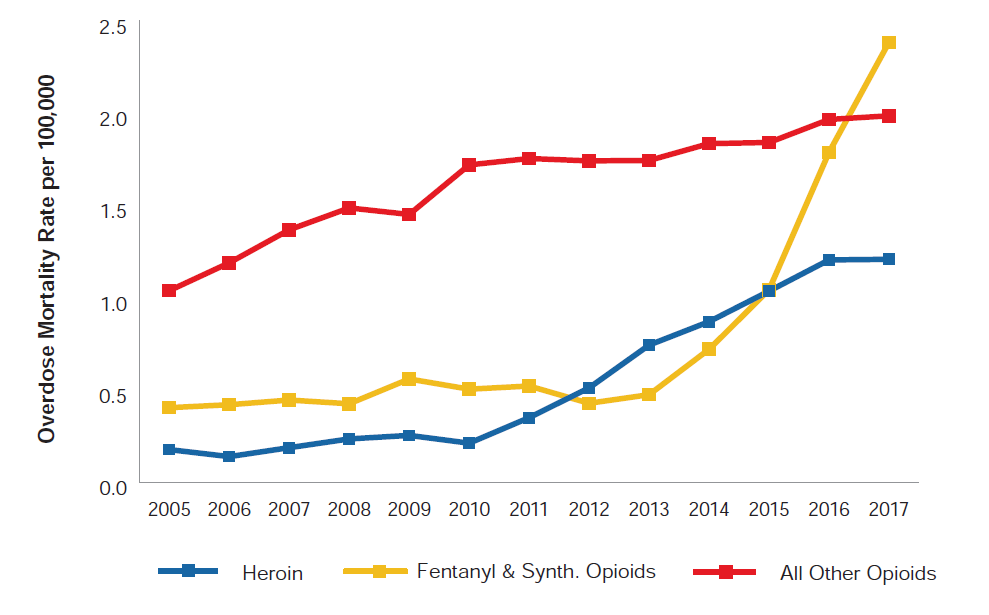

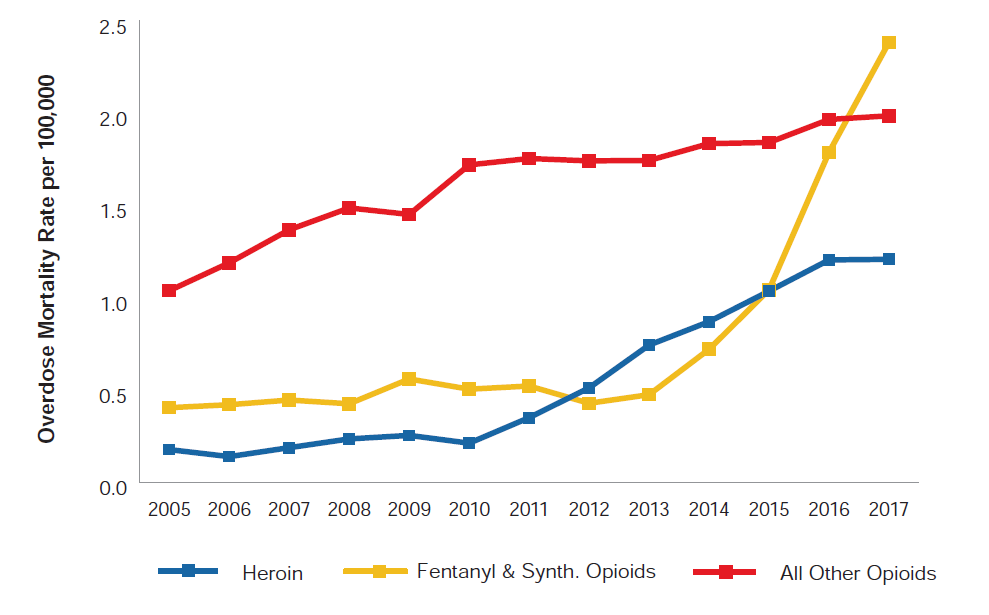

The frontline of the opioid epidemic has shifted in the last decade, moving from one predominantly characterized by prescription opioid overdoses to one increasingly defined by heroin and synthetic opioids. Between 2010 and 2017, overdose deaths in the university-educated population over the age of 25 involving heroin and synthetic opioids rose from 7.6% to 25.5% and from 18.1% to 50.3%, respectively. Meanwhile, overdoses involving other types of opioids fell from 62.0% to 41.9%. Note that the sum of these proportions exceeds 100% because multiple causes of death can be assigned to a single death. From this data, it becomes quite clear that heroin and synthetic opioids have become important drivers in opioid-related overdose deaths. Figure 4 shows how overdose mortality rates have changed between 2005 and 2017 for the university-educated population that is 25 years old or older by the type of opioid involved in the overdose.

Source: RGA analysis of mortality data from the MCOD and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

*Population consists of United States civilian non-institutionalized population with bachelor’s, master’s, professional, and doctorate degrees. Excludes associate, vocational, and occupational degrees.

Synthetic opioids and fentanyl: a new threat

Deaths involving synthetic opioids have been the major cause of America’s acceleration in overdose mortality in recent years. Since 2000, synthetic opioid-related overdose deaths have gone from practically non-existent to contributing to half of all opioid deaths in America. Currently, the most commonly misused synthetic opioid is fentanyl.[7] When used under proper medical supervision, fentanyl drugs are used to treat patients with serious pain or post-surgery, and produce physiological effects similar to those of other prescription opioids.[7] While fentanyl can be legitimately prescribed by a doctor, most of the recent fentanyl-related harms are linked to illegally manufactured fentanyl.[8]

Fentanyl can be extraordinarily concentrated, ranging from 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. In fact, just 2 milligrams of fentanyl can cause a lethal overdose. This remarkable potency makes for easy and profitable trafficking, and can enable drug traffickers to cheaply strengthen their product by adding fentanyl to heroin, cocaine, or illicit pills.[7] This can lead to volatile inconsistencies in the potency of illegal drugs on the market, further compounding the risk of overdose. The dangers of the infusion of fentanyl into the drug supply are reflected in drug-related mortality statistics. Synthetic opioids were involved in about half of heroin- and cocaine-related deaths, and a considerable amount of prescription opioids and psychostimulant (including ecstasy and methamphetamine) deaths in 2017.[2]

The spread of fentanyl is worthy of consideration due to its unprecedented escalation, and because of the risk it adds to consuming other narcotics. Due to the economic incentive for drug traffickers to add synthetic opioids to other illicit narcotics, it is possible that even less dangerous drugs like marijuana could become increasingly hazardous.

Benzodiazepines and co-mortality

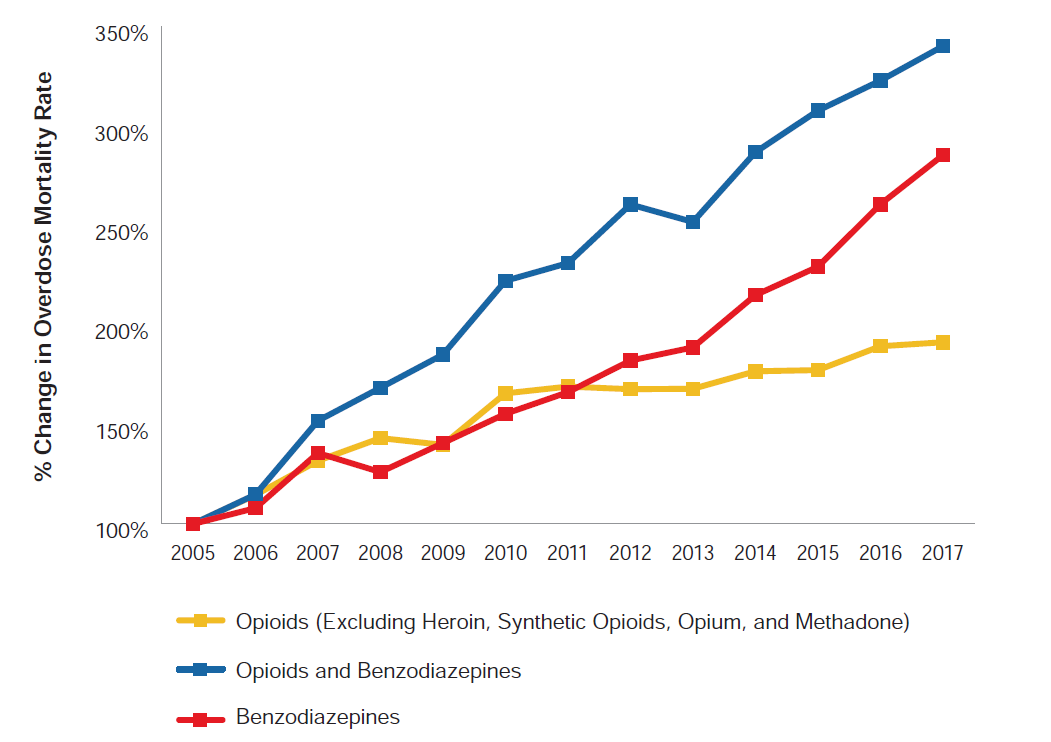

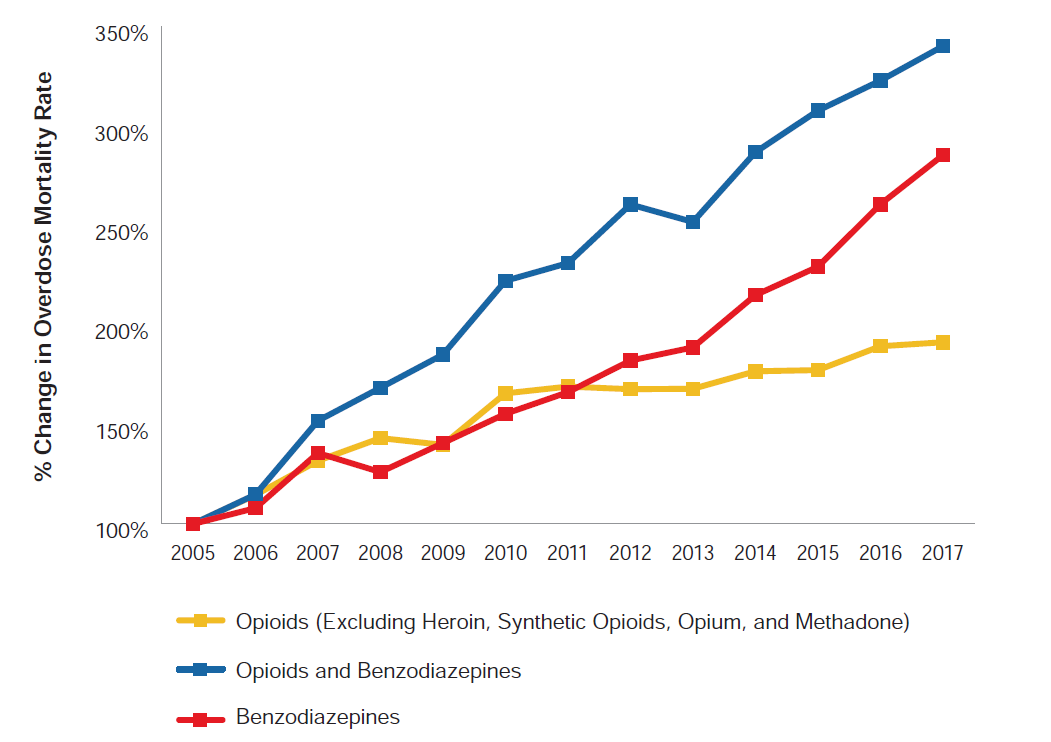

Benzodiazepines are a family of drugs that are prescribed to treat anxiety, depression, and insomnia, or as muscle relaxants. Benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (Xanax) and diazepam (Valium) have become ubiquitous in American life and pop culture as a first line of defense against mental illness and as recreational drugs.[9] Similar to prescription opioids, benzodiazepines are sedative, psychoactive pharmaceutical drugs that are often misused recreationally and have addictive properties. Furthermore, rates of benzodiazepine-related deaths have demonstrated an increase commensurate with that of opioids in the last decade. While opioids and benzodiazepines are distinct pharmacologically, their similar appeal as a recreational drug and the concerning general trends of prescription medicine mortality mean that benzodiazepines and other commonly misused pharmaceuticals certainly should be included in the conversation surrounding prescription drug misuse. Figure 5 shows how overdose mortality rates have changed between 2005 and 2017 for the university-educated population that is 25 years old or older by the presence of opioids, benzodiazepines, or both.

Figure 5:

Change in Overdose Mortality Rates Relative to 2005 by Drug (University Educated, Ages 25+)*

Source: RGA analysis of mortality data from the MCOD and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

*Population consists of United States civilian non-institutionalized population with bachelor’s, master’s, professional, and doctorate degrees. Excludes associate, vocational, and occupational degrees.

In 2017, nearly half of opioid-related overdose deaths also featured a non-opioid narcotic as a contributing cause of death, and almost a quarter included multiple classes of opioids.[2] In particular, the sedative response from combining opioids and benzodiazepines has been linked to staggering overdose mortality; a study of individuals prescribed benzodiazepines and opioids simultaneously demonstrated overdose mortality rates 10 times greater than for those prescribed opioids alone.[10] Analysis of the MCOD shows that benzodiazepines were involved in about one-third of prescription opioid-related overdose deaths in 2017, with the proportion increasing from 21% in 2005. These statistics reveal an alarming link between the concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids and an elevated risk of overdose death.

Prescription opioids: a gateway

Prescription opioids, which include drugs like OxyContin (oxycodone), Percocet (oxycodone and acetaminophen), Vicodin (hydrocodone and acetaminophen), and codeine, have historically been the leading contributing cause of opioid-related overdose deaths in America. Prescription opioids are a common treatment for pain in the U.S. and are generally prescribed for pain attributed to surgery recovery, childbirth, cancer, and chronic conditions. While prescription opioids are an approved and effective treatment for pain, they are highly addictive, particularly when taken for longer durations and in higher dosages.

There is a great deal of evidence that America’s opioid problems were caused, at least in part, by the prescription and subsequent abuse and misuse of legal opioids.[4] Misuse of prescription opioids has been linked to abuse of heroin, fentanyl, and other synthetic opioids; according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 75% of post-2000 heroin users initially used prescription opioids before moving to heroin. [11] Analyzing prescription drug history could provide insurers the opportunity to better understand the relationship between prescription opioid use and all-cause mortality experience.

Prescription Data Analysis

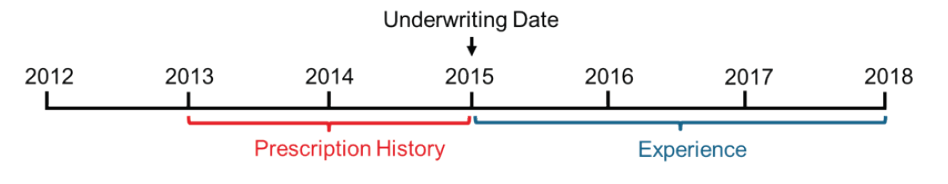

To better understand the risks opioids pose to the life insurance industry, RGA analyzed the relationship between opioid prescriptions and all-cause mortality, using prescription history data. It is important to understand that this analysis does not directly reflect opioid-related overdose mortality.

Based on their prescription history, individuals who were likely being treated for one or more serious illnesses, such as cancer, were excluded from the analysis. These exclusions were designed to remove the individuals who would be declined for life insurance or placed in a high substandard group. Further, the study population was limited to individuals aged 30-69 who were eligible for health insurance coverage.

The study includes prescription history for 3.2 million people, totaling 12 million opioid prescription fills over a two-year period from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014. The analysis compares actual deaths of 15,571 people to expected deaths over the following three years (January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017), where expected deaths account for age, gender, and calendar year. The details of the methodology and study design are in the Appendix.

Statement of limitations

Our dataset does not include full medical histories to allow us to control for existing health conditions directly. Instead, we used information from the prescription histories to infer likely medical conditions and then used this information in two ways. First, individuals were excluded from the study if their prescription history indicated the presence of an underlying condition commonly associated with substantially elevated mortality (e.g., cancer). Second, the expected mortality basis was standardized using the RGA Rx Severity Score to adjust for the expected additional mortality risk resulting from underlying health conditions. However, it is possible that severe underlying conditions are unaccounted for within the data and the mortality adjustments are not sufficient, ultimately producing biased results.

Because the study identifies those individuals with serious health conditions based on prescription history, it is possible that seriously ill people are not identified under the following circumstances:

- The individual is not taking a drug commonly prescribed for the serious underlying condition.

- The prescription is not being billed to the health insurer, and thus is not included in the studied dataset.

Additionally, the prescription of opioids alongside other medications could be an indication of the severity of the underlying condition for which the medication is prescribed. Therefore, some of the elevated mortality in this study can likely be attributed to the severity of the underlying condition rather than the risk associated with prescription opioid abuse. It is further worth noting that the study does not exclusively focus on the extra mortality from overdoses. Additional detail regarding these limitations is provided in the Appendix.

Opioid dosage

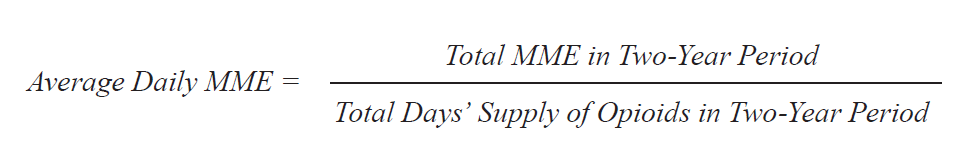

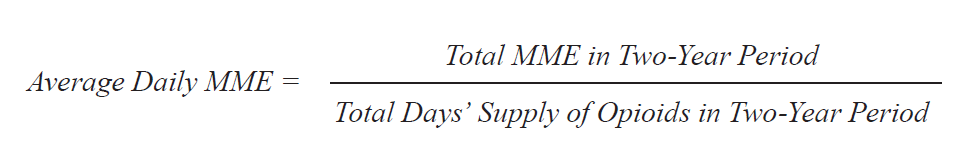

The comparison of dosages across different opioids requires a standardized metric of opioid strength due to the different potencies of each specific opioid. For example, one milligram of morphine is equivalent in strength to 1.5 milligrams of oxycodone, one of the most popular prescription opioids. Throughout this analysis, the opioid dosage is converted to morphine milligram equivalent (MME), a commonly used standardized measure of opioid dosage using conversion factors released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.[12]

The average MME consumed per day is calculated by comparing the total MME consumed by an individual in the two-year period to the total days’ supply of opioids the individual received in the two-year period.

Previous research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that daily MME consumption is strongly linked to increased risk of overdose death.[13]

This study classifies users into one of three groups based on the total days’ supply of opioids prescribed in the two-year period. The majority of individuals had a short-term opioid prescription history, defined as a total days’ supply of 30 days or less. This is likely the result of a single prescription fill. The other days’ supply groups are comprised of individuals who were prescribed opioids more regularly and are designed to distinguish between moderate and long-term use. It is important to note that since we are not looking at an individual’s entire prescription history, it is possible for opioid prescription experience to be misclassified if the opioid prescription history was significantly atypical during our two-year observation period. Figure 6 shows the percentage of total opioid users by total days’ supply prescribed over the two-year observation period.

Figure 6

Total Days’ Supply of Opioids

in 2013-2014 | Percent of Total

Opioid Users

|

1-30 days | 81.2% |

31-120 days | 10.3% |

121+ days | 8.5% |

Average daily MME strength varies by the days' supply group. Those with the highest number of days' supplied also have higher-strength prescriptions. Interestingly, individuals with an opioid prescription duration between 31 and 120 days received a lower average strength than those with opioid prescriptions spanning less than 31 days or more than 120 days. In order to focus our analysis on relevant average daily MME groups, we have split each of the days’ supply groups into six groups based on the percentile of average daily MME within their respective days’ supply group. Figure 7 shows the upper and lower bounds of average daily MME for each group.

Figure 7

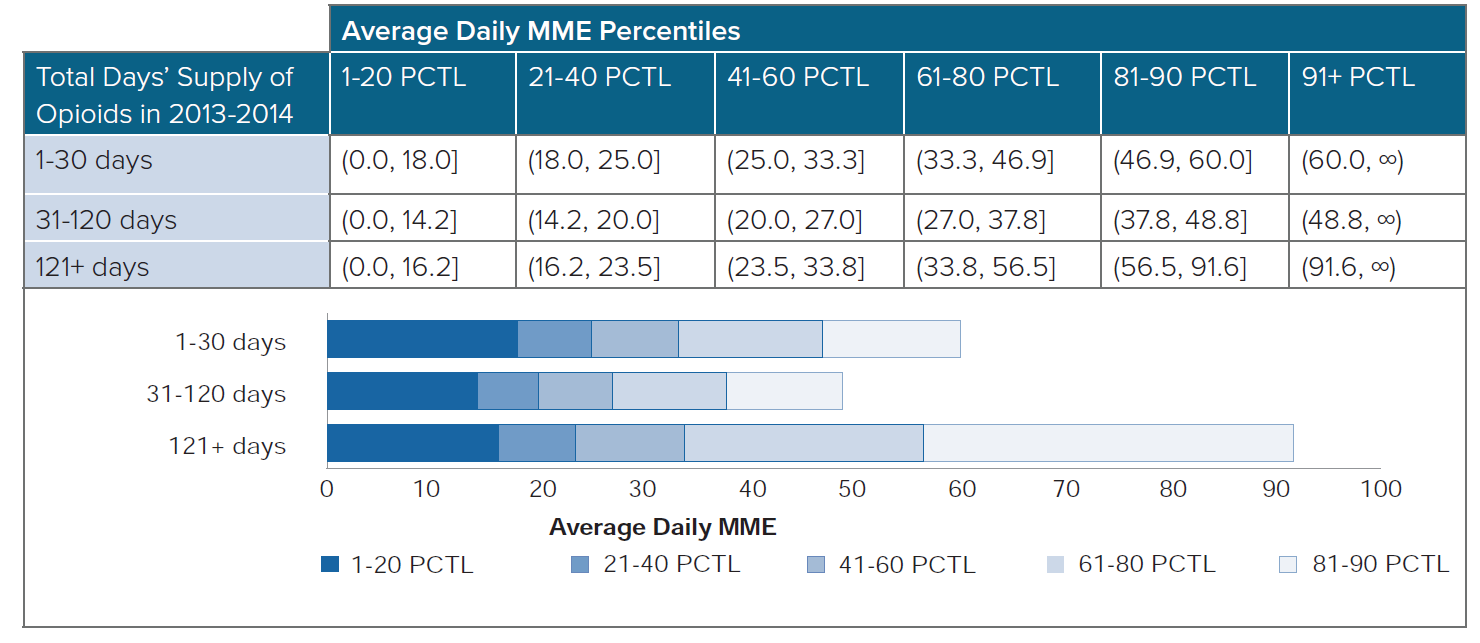

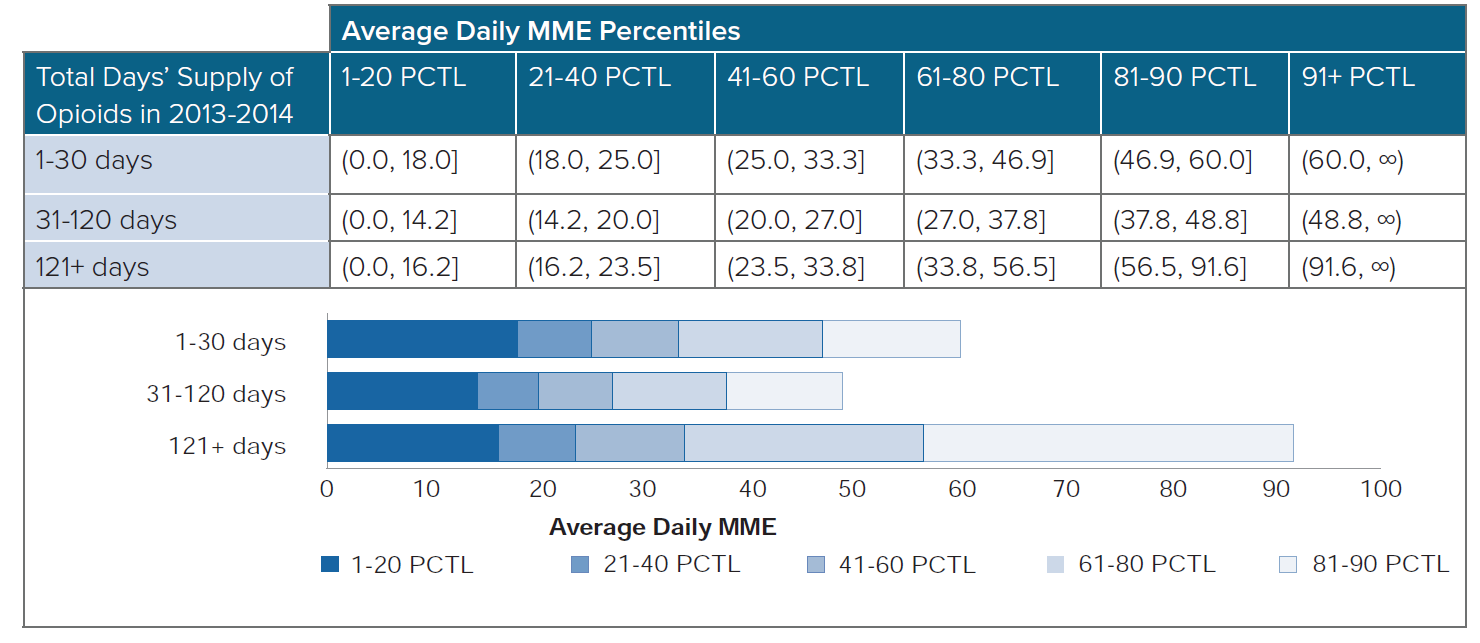

Figure 8 shows the ratio of actual deaths to expected deaths by daily MME percentile and days’ supply group relative to the overall all-cause mortality ratio for opioid users. The shaded areas around the curves represent a 95% confidence interval.

Figure 8:

All-Cause Mortality A/E by Daily MME Percentile and Days’ Supply Relative to Overall All-Cause Mortality for Opioid Users

The analysis shows:

- Higher all-cause mortality experience for longer-term prescriptions for all MME percentiles.

- Very little difference in all-cause mortality experience based on MME percentile for short-term users, who make up more than three-fourths of all opioid prescriptions.

- For those with the highest days’ supply, increasing the daily MME strength was associated with increased overall all-cause mortality by up to 5 times that of individuals with short-term opioid prescription history. Similarly, at the highest levels of daily MME, those with a total days’ supply between 31 and 120 days experienced mortality up to 2.5 times higher than individuals with short-term opioid prescription history.

Type of opioid

Although the potency of opioids can be standardized by converting to MME, there are still differences in how each type of opioid is processed by the body. Due to differences in the chemical structure of distinct opioid types and the various ways in which they can be taken, an equal dosage of opioid in terms of MME can vary in terms of:

- Strength of euphoric effect

- Time to produce a physical response to the drug

- Duration of effect

- Addictive potential

- Likelihood to overdose

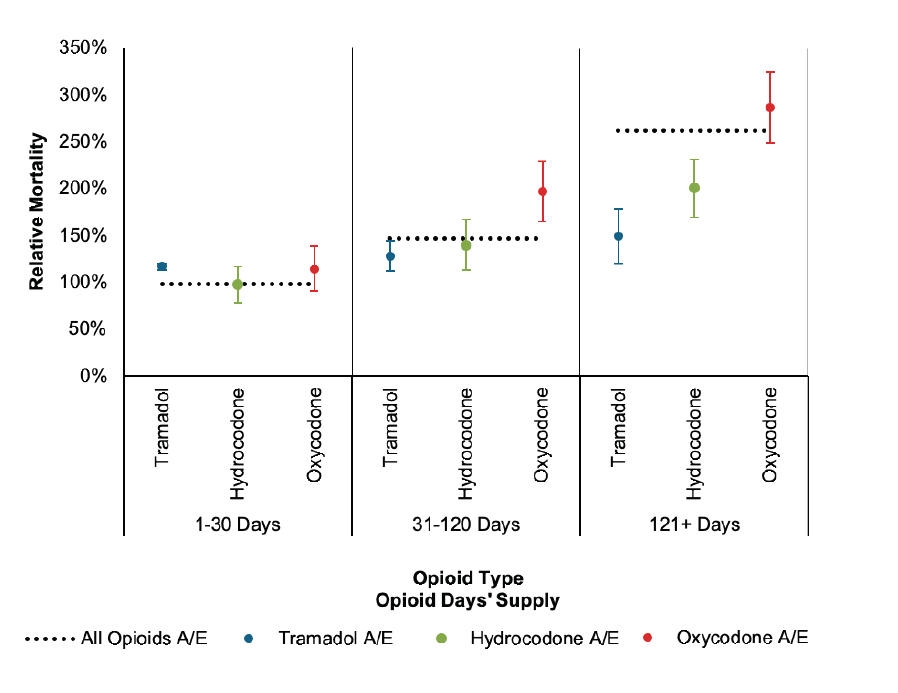

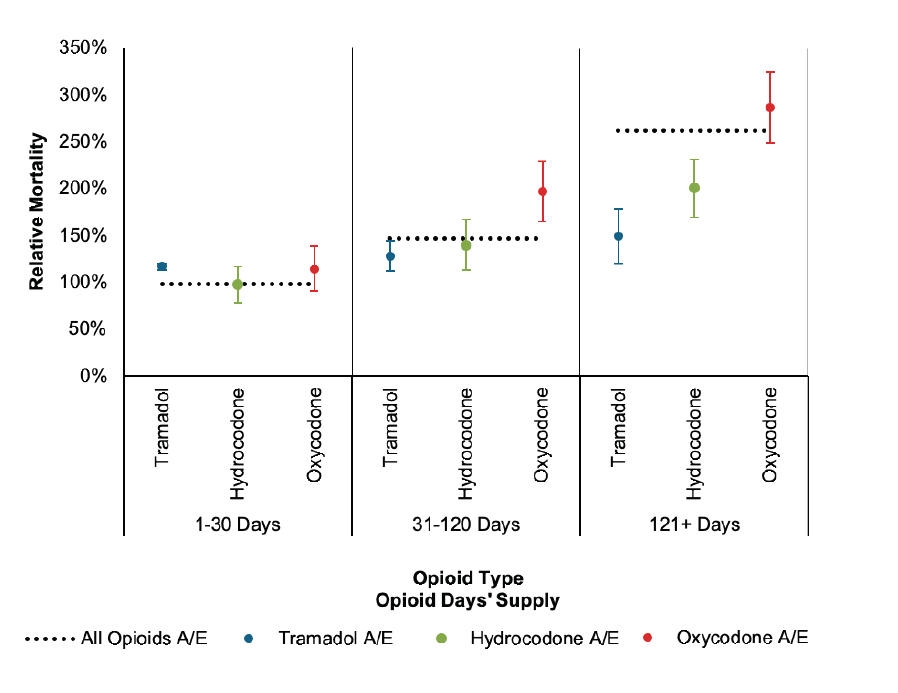

Figure 9 compares all-cause mortality experience by days’ supply group for oxycodone, hydrocodone, and tramadol. Tramadol is of particular interest because it is often considered to be less addictive than other opioids. The days’ supply groups in Figure 9 represent the days’ supply of each specific opioid. Note, it is possible for a single person to be prescribed more than one type of opioid. The actual to expected (A/E) measures are relative to the overall A/E of all opioid users in the study population.

Figure 9:

All-Cause Mortality A/E by Opioid Type and Days’ Supply Relative to Overall All-Cause Mortality for Opioid Users

While there is very little difference in the all-cause mortality experience of individuals with short-term opioid prescription history by opioid type, all-cause mortality experience associated with longer total days’ supply of oxycodone is much worse than that associated with longer total days’ supply of tramadol. While both hydrocodone and oxycodone all-cause mortality experience worsens dramatically as the total days’ supply increases, all-cause mortality experience associated with tramadol prescriptions is relatively constant by total days’ supply group.

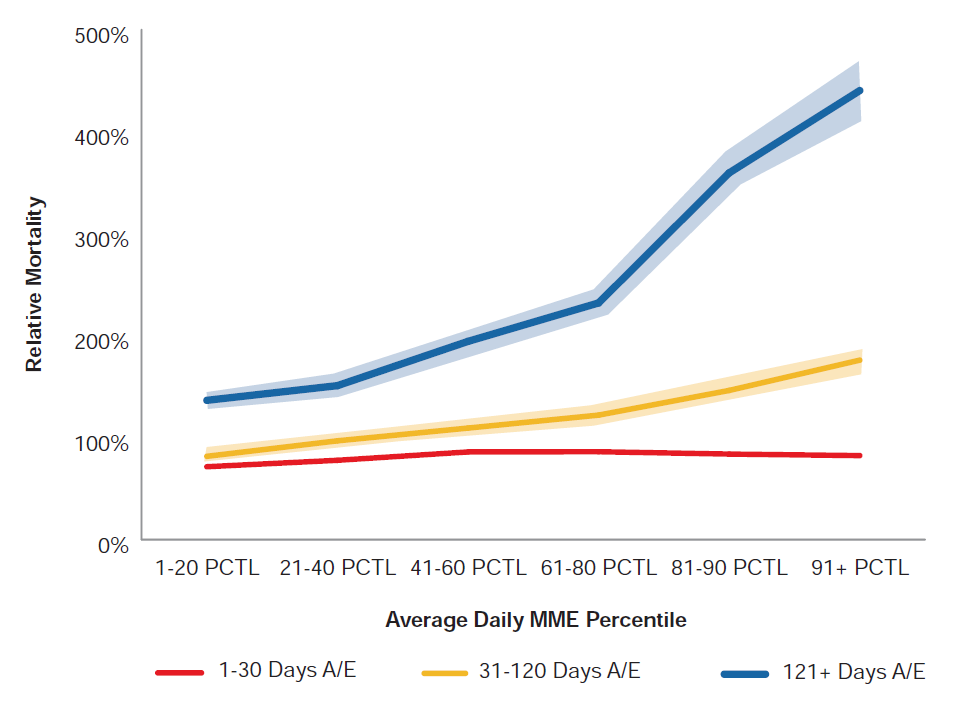

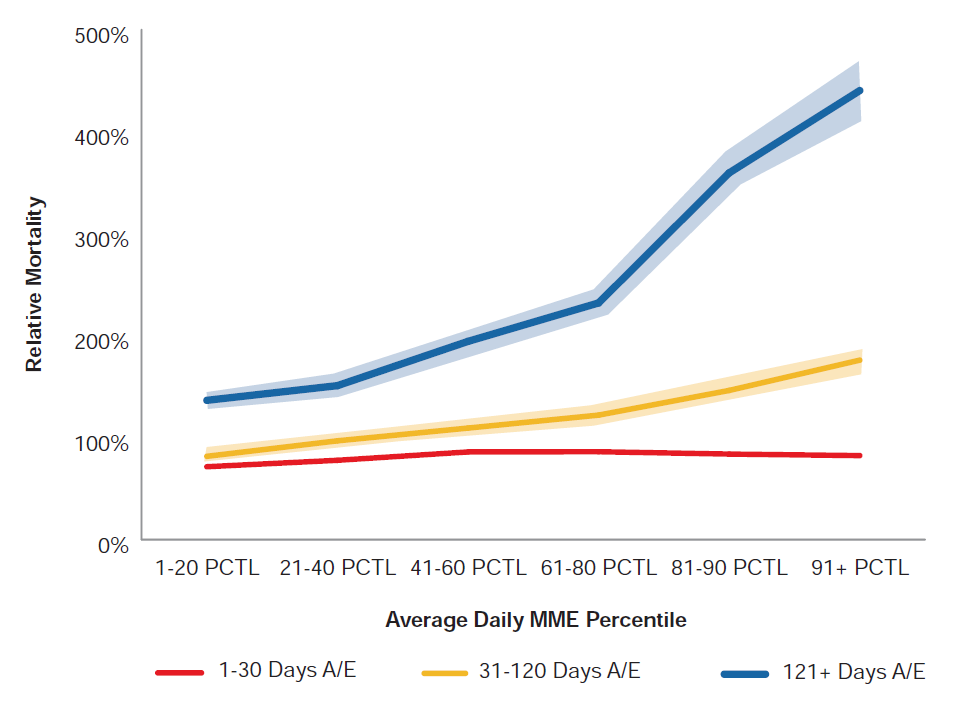

Interaction with benzodiazepines

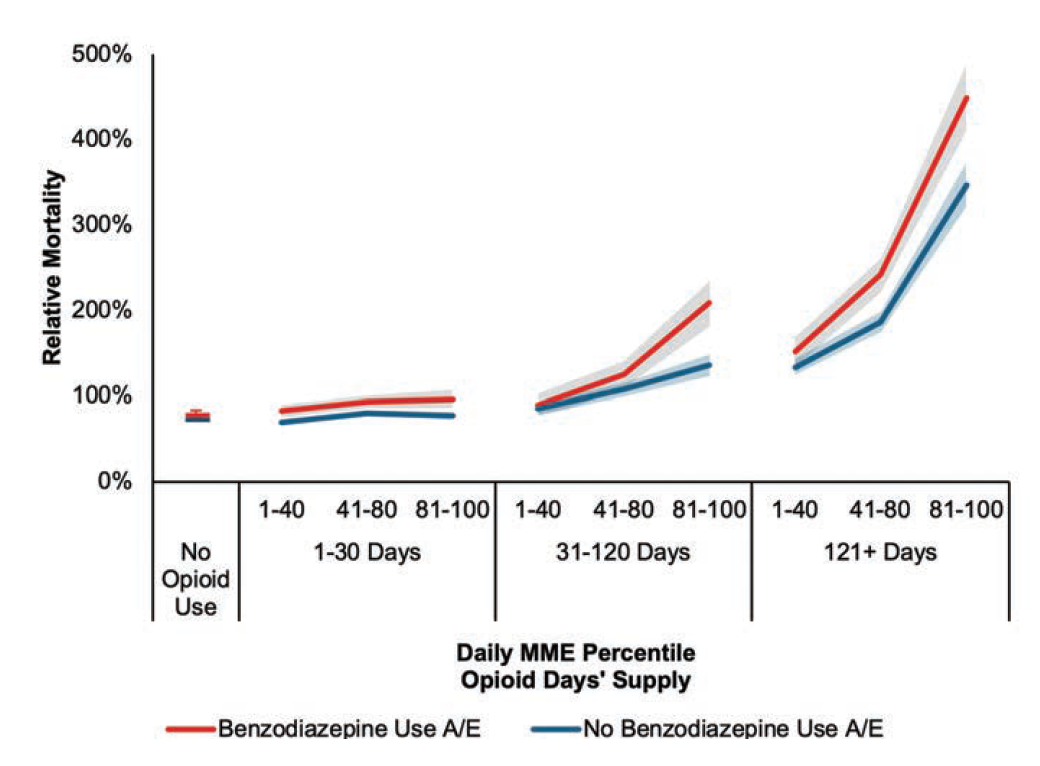

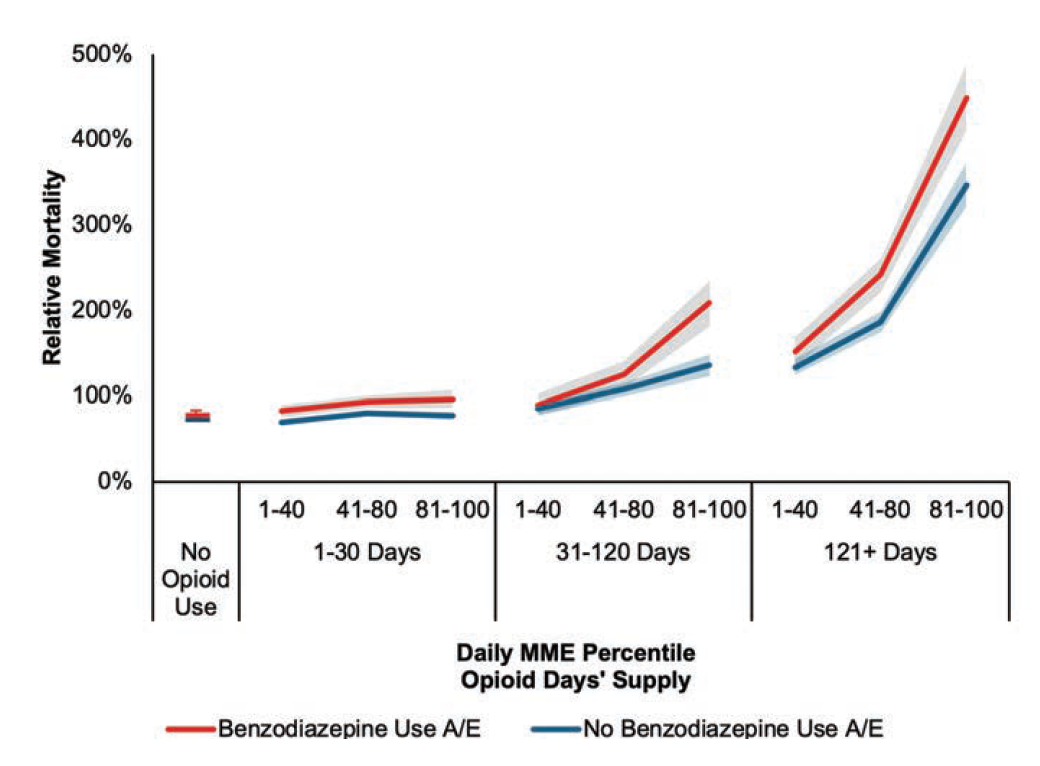

Benzodiazepines, a class of drugs typically used to treat anxiety, are often taken in conjunction with opioids. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “more than 30 percent of overdoses involving opioids also involve benzodiazepines.”[14] In our prescription data, 11.9% of the population received a prescription for benzodiazepines within the 2013-2014 period. Individuals who received a fill for benzodiazepines were over 50% more likely to also receive a fill for opioids than those without a benzodiazepine prescription. Figure 10 shows the impact of mixing benzodiazepines with opioids by splitting our results for opioid usage by presence of benzodiazepines. For reference, the relative A/E for people who have no opioid prescriptions in the two-year observation period is shown.

Figure 10:

All-Cause Mortality A/E by Opioid Daily MME Percentile, Days’ Supply, and Presence of Benzodiazepines Relative to All-Cause Mortality for Opioid Users

All-cause mortality experience worsens with increasing prescriptions of both opioids and benzodiazepines. The prescription of 121+ days’ supply of high-strength opioids alongside benzodiazepines is associated with nearly 6.2 times the all-cause mortality experience of individuals taking neither opioids nor benzodiazepines; people without a prescription of either drug type have a relative all-cause mortality risk 28% lower than those prescribed opioids. The concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines, especially at high levels of both drugs, is an important consideration for underwriters assessing an insurance applicant’s risk.

All-cause mortality experience worsens with increasing prescriptions of both opioids and benzodiazepines. The prescription of 121+ days’ supply of high-strength opioids alongside benzodiazepines is associated with nearly 6.2 times the all-cause mortality experience of individuals taking neither opioids nor benzodiazepines; people without a prescription of either drug type have a relative all-cause mortality risk 28% lower than those prescribed opioids. The concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines, especially at high levels of both drugs, is an important consideration for underwriters assessing an insurance applicant’s risk.

Conclusion

Although the future scope and duration of the opioid epidemic are difficult to anticipate, there is reason for optimism: Preliminary 2018 reports from the CDC show a slight drop in opioid-related overdose mortality, ending a troubling decade-long rise.[15] That said, opioid-related overdose mortality rates remain near historically high levels, and a continued rise of synthetic opioid overdose mortality demonstrates that opioid misuse could continue to be a standard component of all-cause mortality experience in the future.

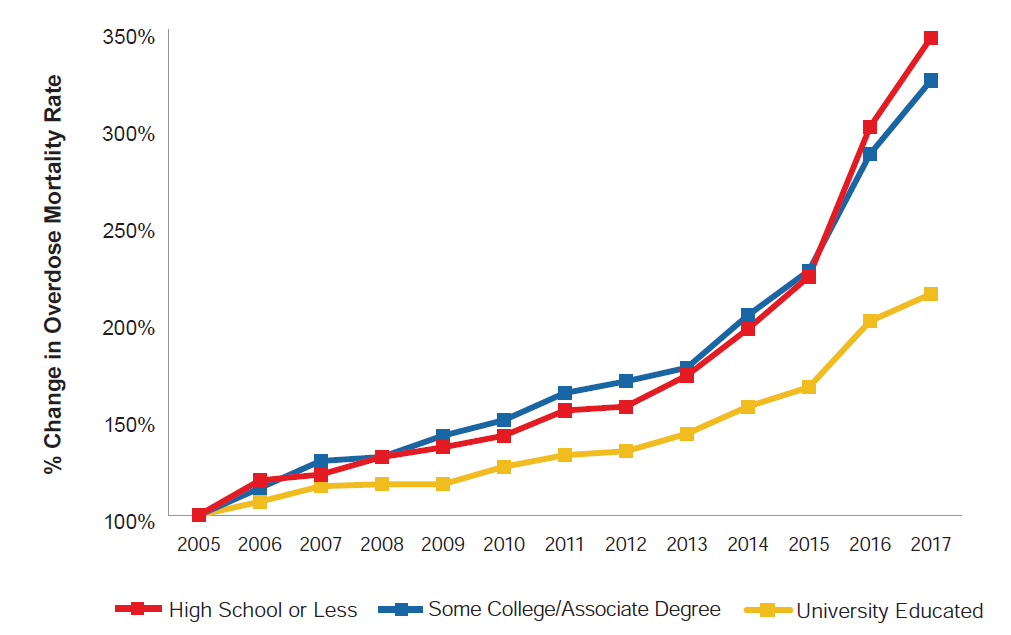

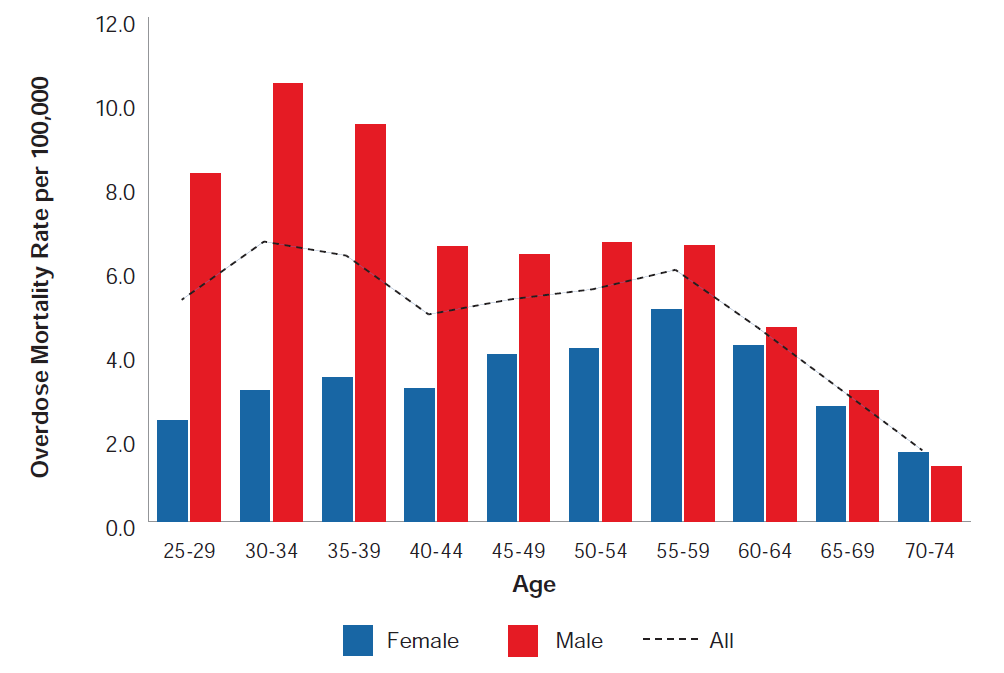

This rise of opioid-related overdose mortality in America is undoubtedly a challenge that threatens Americans of all socioeconomic statuses and age groups, albeit to different degrees. While there are certainly limitations with using age and education level as proxies to estimate the experience of the insured population, opioid-related overdose mortality rates are considerably lower for people with higher levels of education. However, worsening opioid-related overdose mortality trends among older, educated Americans should be of interest to insurers.

The aim of our prescription drug analysis is to better understand all-cause mortality associated with prescription opioids. Our research shows much worse all-cause mortality experience for those with longer-term prescriptions. However, this analysis found no increase in all-cause mortality experience for the vast majority of patients who have a prescription of opioids lasting less than 31 days, regardless of the strength of the prescription. There are also differences in all-cause mortality experience based on the type of opioid prescribed. People who received prescriptions for oxycodone and hydrocodone showed elevated all-cause mortality risk as the days’ supply of these drugs increased. Conversely, an increase in days’ supply of tramadol was not associated with an increase in all-cause mortality risk. Additionally, there is evidence of worse all-cause mortality experience for those who are prescribed both benzodiazepines and opioids, especially with longer-term usage.

The current state of opioid-related overdose mortality in the United States is dire, but there has been some positive change. Government agencies have taken decisive stances against opioid misuse, while revised guidelines for treating chronic pain have contributed to a considerable drop in prescription opioid consumption in America from its peak in 2011. Furthermore, preliminary reports show that drug-related mortality plateaued in 2018, though many of the improvements appear to be offset by rises in mortality related to other narcotics.[15] These emerging reports are welcome after more than a decade of worsening opioid-related overdose mortality, though the future remains unclear. What is clear is that opioid misuse affects Americans of all demographics, though individuals from the older, more educated demographics traditionally covered by life insurers have comparably lower risk.