Trust in Latin is fides, literally translated as “good faith.”

Perhaps no other word better describes the business of life insurance. The policyholder must take faith in a largely intangible promise – a pledge that the insurer will protect sensitive information and pay benefits should a claim event arise.

As the industry digitizes and gains access to new sources of data, such trust in the integrity of insurers has become critical. Data and analytics are transforming the industry. From risk selection to product design, the opportunities to improve the insurance process are nearly endless, but all require insurers to collect larger volumes of personal data on their customers.

So, it is especially disconcerting that consumer faith in insurers reached a new low in 2018. Edleman’s “Trust Barometer” survey asked 1,150 respondents in each of 28 markets to rank industry sectors they most trusted with personal data. The report has consistently revealed financial services to be the least trusted of the major industry groups, trailing technology, health care, energy, and entertainment sectors – all of which have been subjected to high-profile and headline grabbing cybersecurity incidents. Even within the financial services category, the insurance industry is among the least trusted sectors and consistently ranks below banks, credit card companies and other payments industries.

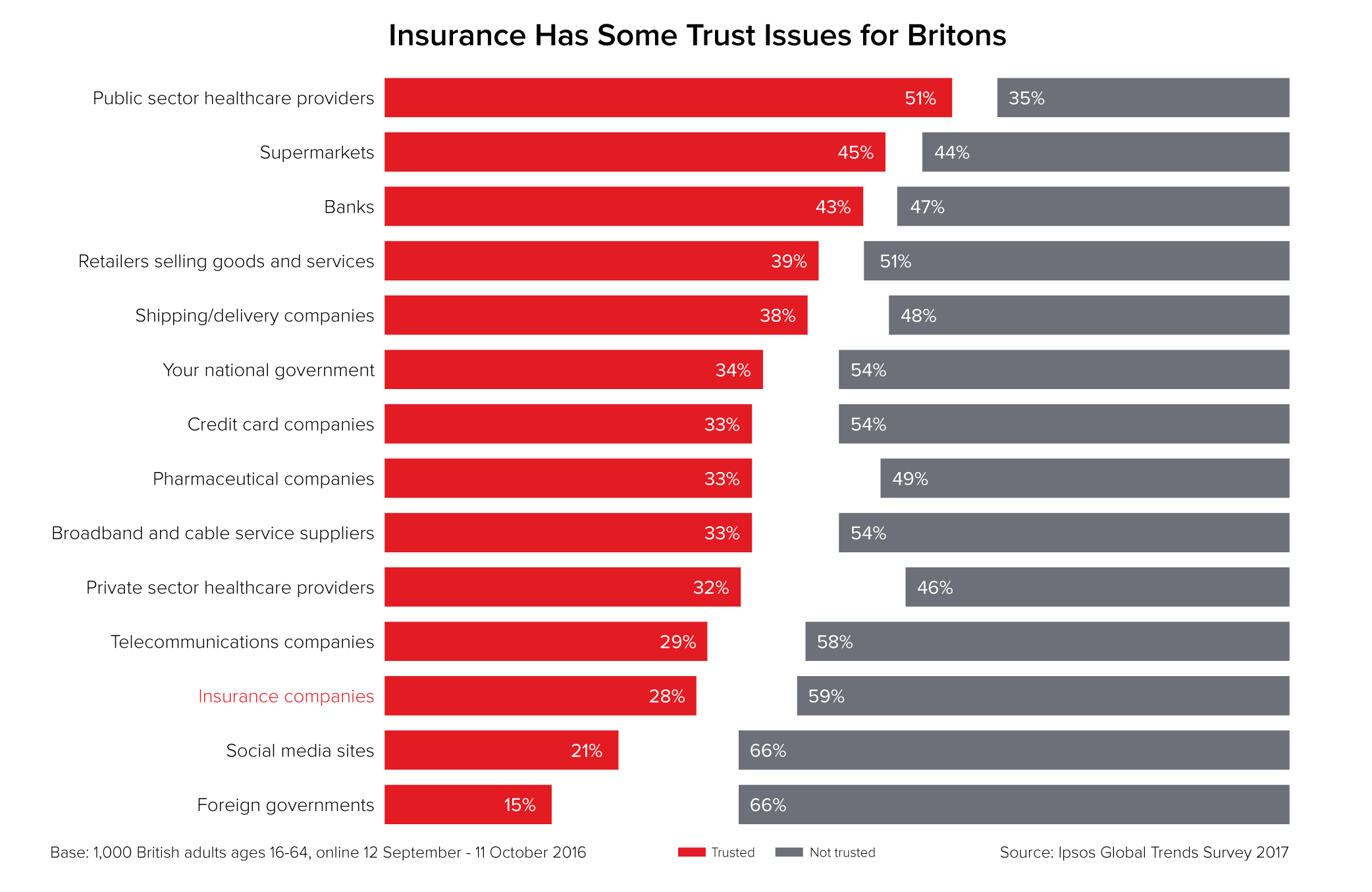

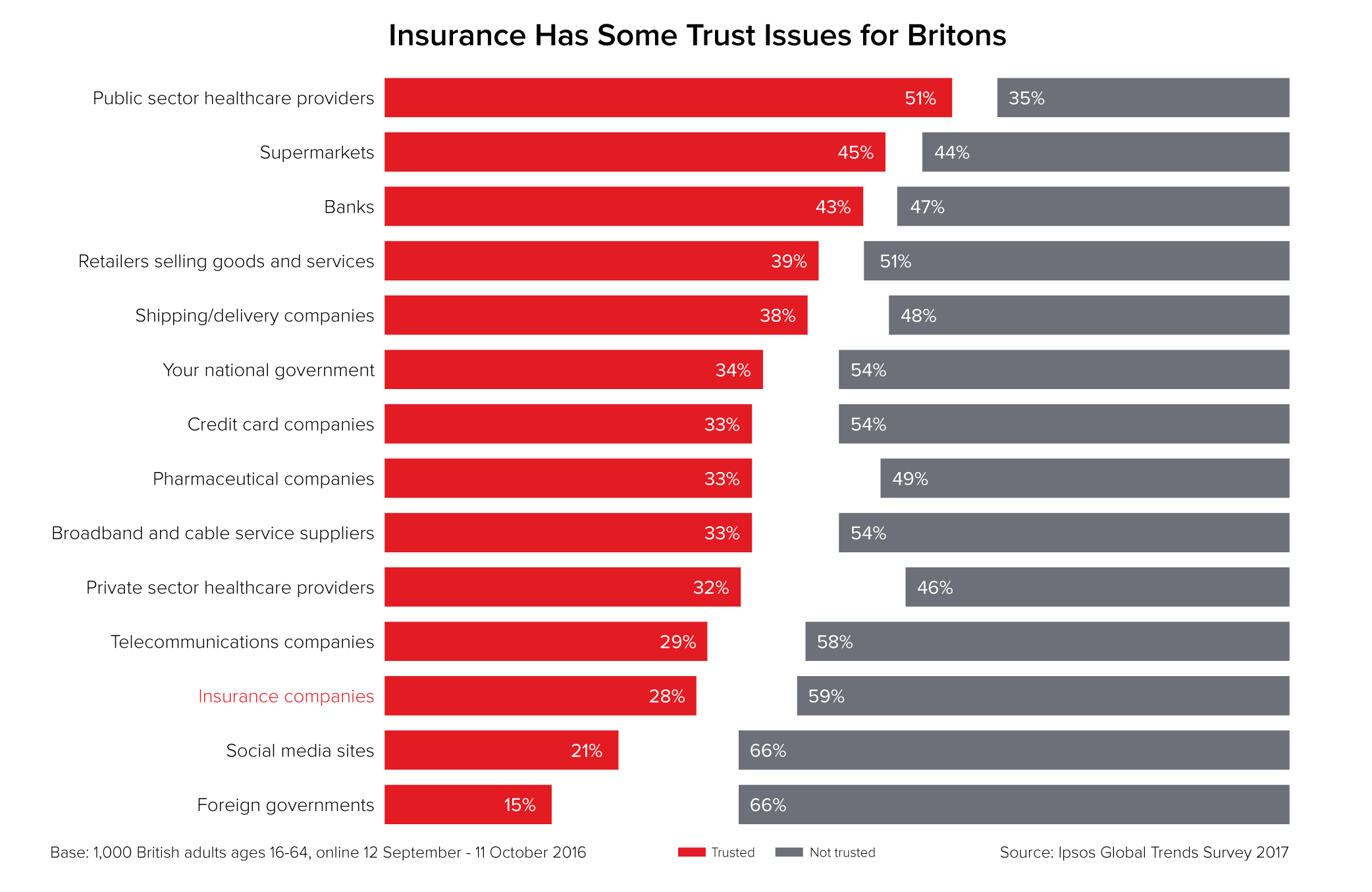

Other research confirms these findings. In 2015, IBM’s Watson Customer Engagement survey asked participants, “Do you trust your insurance company?” Fewer than half answered yes. In 2017, the statistics giant You.Gov surveyed U.S. consumers and found that only 10% trusted insurers “a lot.” And an Ipsos Global Trends Survey (shown below, click to expand) in the U.K. found that trust in insurers was lower than in banks, credit card companies, and telecom.

Evidence suggests mistrust has already cost carriers. Consider Usage-Based Insurance (UBI), a type of auto insurance that links premiums to mileage and driving behaviors. In 2013, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners cited privacy as the main obstacle to adopting UBI. While insurers have sought to use data analytics to increase efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance coverage, many consumers have determined the benefits may not be worth the perceived risks.

A Transparent Solution

How can insurers halt, or even reverse, this reputational decline? Technology giants offer one path forward. After all, Internet, hardware and social media giants may deliver amazing convenience with every keystroke, but these advances can come with unintended costs. The non-profit Identity Theft Research Center reported a 126% increase in 2018 of security incidents exposing the sensitive personally identifiable information of U.S. consumers.

It is little surprise that the phrase “techlash” was runner-up for the Oxford Dictionary’s word of 2018. Techlash is the “strong and widespread negative reaction to the growing power and influence that large technology companies hold,” and reflects growing public unease and regulatory scrutiny following the unintentional loss or unauthorized release of personal data by tech companies. Still, year after year, the tech sector continues to retain more trust than any other in Edleman’s survey.

What explains this contradiction? Transparency. Every day, these enterprises must perform a delicate balancing act. They rely on data-based insight to provide highly customized services, while also seeking to empower customers to control access to this data through communication and tools. Consider Apple’s plain-language privacy disclosures and transparency reports, both of which are packed with simple charts and bullet points. Wearables giant Fitbit publishes a bulleted list of links in an effort to demystify privacy policy legalese. And search behemoth Google has long offered a privacy and security dashboard that summarizes user activity and provides the consumer with options to withhold certain details.

The approach appears to be working: 94% of the 2,000 customers responding to a 2019 study by software-as-a-service provider Label Insight identified transparency – not privacy – as the number-one factor motivating brand loyalty.

Traditional insurers offer nothing like this degree of openness. Communication is one-way, with underwriters gathering personal data and yet providing no indication of how this information is being assessed or used. Applicants either receive an acceptance or rejection, with little clarifying detail, and policyholders rarely hear again from the insurer until claims time.

This does not bode well as the industry attempts to improve risk assessment and expand into underserved markets. Data analytics can empower insurers to unlock insights into ever smaller groups and employ highly accurate, granular pricing models. Accessing this wealth of information, however, requires trust built over time. The industry must resist the temptation to rely on impenetrable algorithms that cannot be easily explained, and insurers must significantly improve the frequency and quality of customer communication. The first to provide customers with greater control of personal data will likely be more trusted and earn the right to expanded access.

Insurtech startups appear to have received the message. Many are focused on presenting themselves more transparently than established insurers. The carrier Lemonade, for example, publishes “Transparency Chronicles.” By positioning themselves as a response to more established insurers, these new entrants have successfully developed significant levels of trust with early adopters in target markets, especially among the coveted and tech-savvy millennial demographic.

A Societal Debate

As the amount of personal data increases, so do the protections provided to consumers and resulting compliance obligations. Most notably, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) creates a sweeping set of data laws across the whole of the EU. Modernized data protection laws are a global phenomenon with new laws either recently enacted, or soon to be enacted, in Japan, Taiwan, and South Africa, to name a few.

The insurance industry and associated professional organizations must prove the relevance of data to risk prediction and engage in a broader societal debate on the value and future of insurance. This will require carriers to address concerns about purely correlational relationships or the potential for certain proxy variables to unintentionally be used to make rating decisions based on protected or socially unacceptable factors such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, or educational attainment.

The extent of risk pooling that is considered fair is also intensely culture specific. In some countries, fairness is about paying a price that most accurately represents the risk a specific consumer brings, which must be absorbed by the pool of other insureds. This results in a tendency for more complex rating approaches and smaller pools of risk that minimize cross subsidies. Increasing levels of information about an applicant increases the possibility smaller risk pools. Smaller risk pools have the potential to price poor risks out of the market and nobody wants to reduce the size of the addressable market so a socially acceptable balance needs to be found.

The opposite view of fairness is that large cross subsidies are desirable because it means more people have access to insurance at the similar price, promoting social solidarity and inclusion. Community rating, where all people in a given territory are given the same price without underwriting regardless of their health, are an expression of this end of the spectrum.

The other aspect of fairness is that people do not abuse the system, to ensure the many don’t pay more to cover the few that lie or commit fraud. Insurers must have access to the same data pertaining to risk that is available to applicants. Information asymmetry springs from a consumer gaining more data on their probability of claiming than the insurer has, perhaps through a direct-to-consumer genetic test or other method. If the consumer has a mechanism to evaluate that data with respect to potential risk, and withhold that information from the insurer, anti-selection arises. Those at higher risk extract more value from the insurance pool and drive up costs for everyone else. It’s a question of basic fairness to begin, but at the extreme, it can also render voluntary insurance systems unviable. Everyone suffers.

A Customer Conversation

Meeting consumers’ privacy expectations requires an ongoing relationship – and not a one-time exchange of information. When insurers regularly engage with consumers, it provides more opportunities to demonstrate value and build trust. By using customer data in these engagements, insurers are importantly also implicitly renewing consent.

How can the life and health industry increase the number of value-adding interactions? One solution is the incentivized wellness concept pioneered by the South African company Discovery and exported around most of the world as “Vitality.” As part of the Vitality program, actions taken by the insured and insurer create shared value: the customer lives a longer, healthier life and the insurer reduces the probability of a claim.

This alignment of interests, in itself, builds trust and understanding. Consumer data is regularly used to generate health scores, providing the insurer with more frequent reasons to connect with the customer. The consumer freely provides more lifestyle-related health data through the interactions and a relationship is built over time. The program also clearly explains how the data it uses translates into insurance discounts and other consumer benefits. To access interventions and services available, insureds are incentivized to provide additional risk-specific data.

A Reality Check

While insurance-linked wellness programs like Vitality seem exciting, the outcomes could be less so. Any new apps or reward scheme must enter a crowded market. Consumers on average use 10 different apps daily and 30 different apps a month, while also belonging to more than a dozen different loyalty plans. Is there room for yet another?

Insurers must determine the level of engagement consumers expect – and add tangible value, such as rewards that touch everyday activities like buying a coffee or cinema tickets. Pricing such schemes presents another problem, given that insurance is a relatively low-margin business. Many schemes can provide generous benefits to a small number of members only if large numbers pay but do not qualify for benefits. This position will likely prove difficult to sustain over the long term. Given these realities, bundling insurance with other services as part of an existing scheme might enable insurers to benefit from some transference of trust at a lower cost and with less risk.

The continued growth of data and analytics seems inevitable, but all companies must tread carefully, and none more so than insurers. The use of data and algorithms raises fundamental ethical questions about fairness and inclusivity, and requires a leap of faith on the part of the insured. The industry must constantly ask itself, “Just because we can, does that mean we should?”

Life policies are premised on the idea of human worth and designed to preserve dignity during our darkest moments. Honest, transparent, and frequent engagement with customers will enable insurers to demonstrate this unique value, rebuild trust, and earn the right to use data to provide better protection to more people.