In 2018, there were approximately 42 million adults (0.8% of the global population) who owned more than US$1 million of net worth, and whose combined net worth was about US$142 trillion, equating to 44.8% of global wealth.

Of countries with the highest average wealth per adult, the US is ranked third with an average wealth of US$403,974 per adult in 2018. The US has the highest amount of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (UHNWI), numbering about 70,540 people with net assets above US$50 million, representing 49.1% of the total UHNWI population. China is now in second place with 16,511 UNNWIs.1

Mortality may be indirectly influenced by occupation, in part rationalised by education and income and may vary according to lifetime wealth. The HNWI is keen to increase their longevity but many of the wealthy are not prepared for unexpected changes in health. It would appear there is a large gap between what is desired in old age and what has been planned for. This leaves scope for life insurance products to potentially fill this gap.2

Lifestyle and social engagement

As societies have become wealthier, diets have become calorie-laden and salt rich. The European Society for Cardiology reported that obesity in the eastern providence of Shandong, China had risen from just under 1% in both sexes in 1985 to 17% in boys and 9% in girls by 2014. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are now responsible for 60% of deaths and this figure is expected to rise to 71% by 2030. Cancers are occurring more frequently, the incidence of cardiovascular disease is expected to rise by 40% and diabetes is expected to rise by 60%, in part as a result of lifestyle choice.3

A low risk health profile (healthy, rich social network, one or more activity) can increase life expectancy by five years for female lives and six years for male lives. The Leisure World Cohort Study showed that any amount of activity at all resulted in lower mortality compared to those who spent no time doing an activity.The Italian Silver Network Home Care Project separately reported active participants were half as likely to die early compared to those with no or low levels of activity.4 Providing incentives to maintain physical activity could encourage insured lives to continue such activity into later life.

Education, income, wealth, and life expectancy

Wealth differs from income in that it is the cumulative amount of resources amassed over a lifetime, whereas income refers to the flow of money into a household. The association between income and life expectancy was examined in a US study in those aged 40 to 76 years over a 15-year time period to 2014. There were four primary findings:5

- Higher income was associated with greater longevity in all income distributions.

- Inequalities in life expectancy increased over the time period.

- Life expectancy for low-income earners varied significantly within local areas.

- Geographic differences in life expectancy for those in the lowest income quartile were significantly correlated with health behaviours such as smoking, but not with medical care, physical environmental factors, income inequalities or employment conditions.

In the US, the difference in life expectancy between the poorest and richest 1% is now 10.1 years for females and 14.6 years for males. The proportion of total income going to the top 1% of earners has more than doubled from 1970 and since 1986, the top 0.1% of households (>US$20 million in assets) has amassed nearly 50% of all new wealth and holds as much wealth as the bottom 90% combined. For the top income quartile, the strongest correlations to life expectancy were health behaviours such as exercise.6

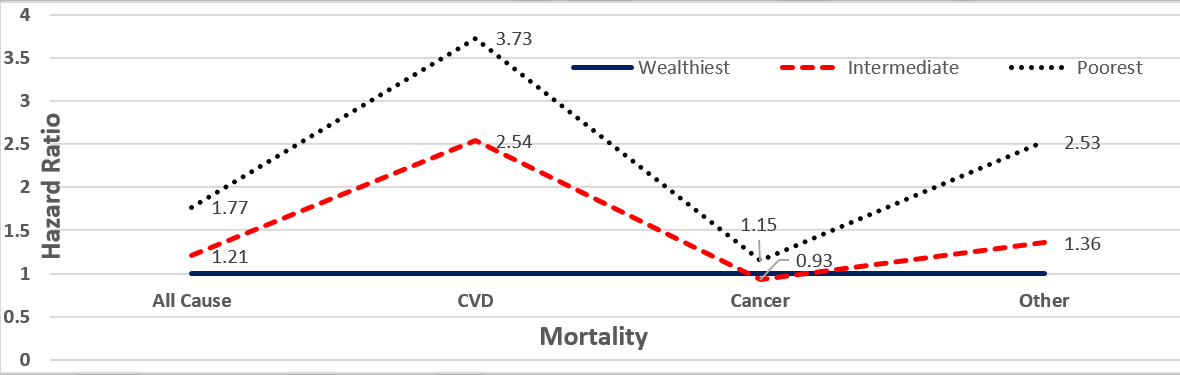

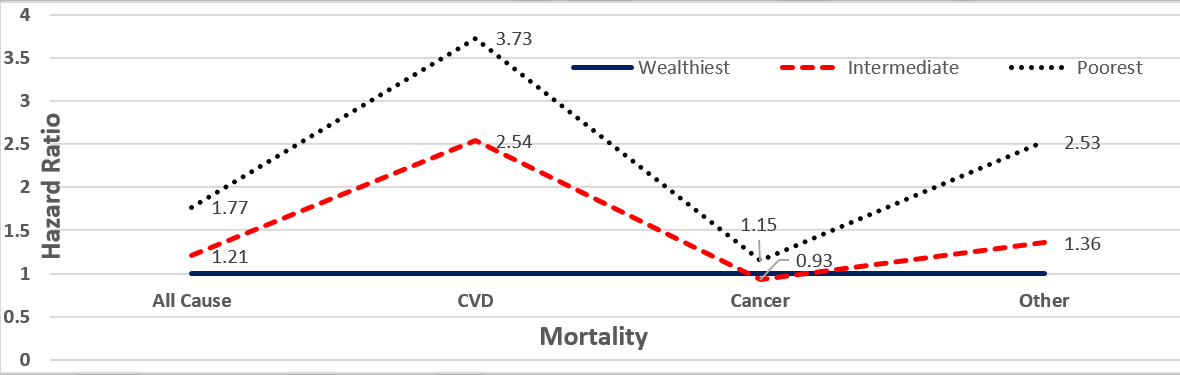

Wealth appears to be more strongly associated with life expectancy than any other socioeconomic measures. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing reported that the lower a person’s wealth, the more likely the person was to be older, female, single, a smoker, physically inactive, depressed, obese and of lower socioeconomic position. Wealth is most strongly associated with mortality from cardiovascular disease, as illustrated in the graph below.7

Figure 1: The association between household wealth and all-cause and cause-specific mortality 50-64 years of age

The relationship between income and suicide

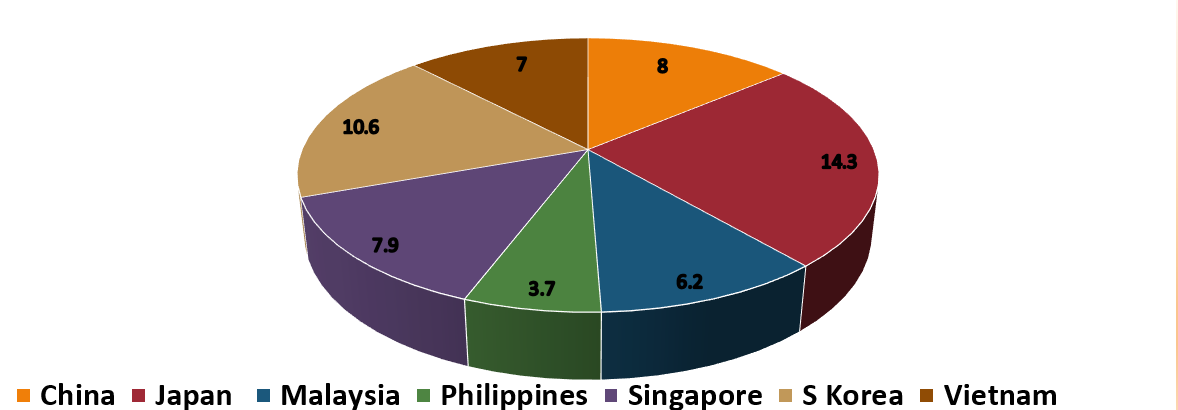

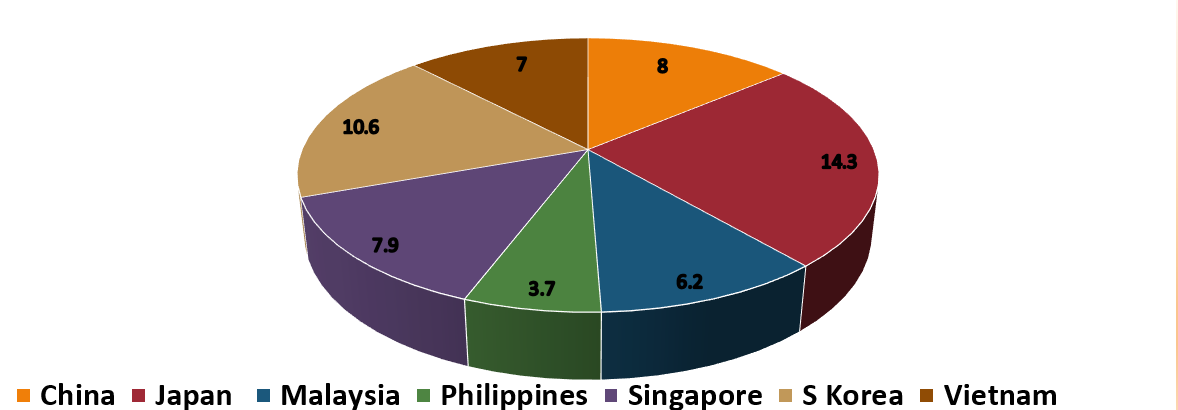

Several studies have found associations between the amount of earnings and suicide rates. During the 1990’s when the Japanese economy collapsed, suicide rates spiked in middle aged men, and overall rates increased by 35% to 32,000 cases. Suicides in South Korean men over age 65 have risen fivefold between 1990 and 2009, from 14 to 77 per 100,000; the country has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.8

Figure 2: Suicide rate estimates, age-standardized per 100,000 population, WHO 20169

However, according to a new study published in the British Medical Journal earlier this year, while the total number of deaths from suicide increased by 6.7% between 1990 and 2016, age standardized mortality rate for suicide decreased by 32.7% worldwide.10 Mental illness continues to affect young affluent individuals, a condition referred to as ‘affluenza’, made famous by the case of Ethan Couch, a son of millionaire parents who killed four and injured nine in a drunk driving incident. New treatment facilities such as Paracelsus Recovery in Switzerland, which specialises in treating ultra-high net worth individuals have emerged. Young wealthy individuals are increasingly using anti-depressants, drugs and alcohol as a coping mechanism for stress and mental pressure caused by managing vast sums of money. The problem is so great in the Middle East that an estimated 80% of young HNWIs regularly take anti-depressants.11

Dementia and ageing populations

According to WHO, the number of people living with dementia is predicted to increase to 82 million by 2030 from the 2018 estimated figure of 50 million. The World Alzheimer Report 2015 estimated approximately 9.5 million people in China were living with dementia, representing 20% of the total world population diagnosed with dementia. Projections suggest that the number of dementia patients in China will rise to 16 million by 2030.12 At the current rate of ageing, China will experience the same change in population ageing in 25 years that took 115 years in France. Other countries experiencing similar trends in ageing include Bangladesh, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. Germany, Italy and Japan are all considered ‘super-aged’ countries, where more than one in five people are over the age of 65. Other countries expected to become ‘super-aged’ by 2030 include Canada, Cuba, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and the UK.13

Life insurance products that financially support long term care of the elderly, including products that offer benefits on diagnosis of dementia could prove profitable. Paid homecare, particularly in Asia Pacific, is more common in wealthier areas with over one third paying for care of dementia sufferers. HNWIs are easily able to afford care in a private nursing home, unlike those on low incomes where family members often have to give up work in order to look after an elderly or sick relative.12

Travel and medical tourism

Research indicates that the number of HNWIs travelling for the purpose of health and medical treatment is growing year on year, driven by low-cost care abroad, cheap flights and shorter waiting lists. It is estimated that approximately 1.9 million Americans will travel outside of the US for medical care in 2019. Top medical tourism destinations include Costa Rica, India, Israel, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey and the US. Many HNWIs travel abroad due to poorer quality treatment at home, for example due to the unavailability of new drugs or a lack of medical technology in their home country. Elective medical treatments include preventive care and rehabilitation services as well as cosmetic surgery, dental treatment and reproductive assistance. Health tours aimed at increasing longevity include everything from gene testing, anti-ageing injections, early stage cancer detection and physical check-ups.14

The modern-day HNWI is drawn to healthcare and wellness products that are unique to the market and are keen to ‘self-gift’ themselves with personal care devices and mobile applications. Many consumers of such products engage via online marketing or social networking sites, while others are reached via private banks, insurance companies or private high-end clubs where medical trips are offered as a value-added service.15 Medical tourism is predicted to be one of the big growth engines of the South Korean economy and there is increasing interest, particularly by the affluent class in China in South Korean culture, known as Hallyu or Korean Wave.16 Even after taking into consideration the cost of travel and hotel accommodation, many medical procedures are still vastly cheaper outside of the HNWIs home country.

Conclusions

The HNW population’s life expectancy is higher than those of lower socioeconomic status. Mortality is influenced by income as well as wealth, in part as a result of level of education and occupation. The rapidly ageing population of Asia Pacific has led to an increase in the rates of dementia, increasing demand for private care home facilities. In an effort to improve health and extend longevity, the demand for medical tourism has also increased appreciably over the last decade, particularly by HNWIs. Life insurance products that financially support long term care of the elderly, specifically where there is a diagnosis of mental illness or dementia, could be of most interest to this wealthy section of the population.