Critical Illness, as a product, is currently more than 30 years old and has proven vitally important to many markets around the world.

Given the speed at which medical science is evolving, can the product continue to retain its fundamental spirit and still remain sustainable? Over the past decade, it has experienced extensive evolution: new standalone and rider structures as well as new product features have emerged, and the number of covered conditions has grown considerably. The impairment definitions themselves have also undergone substantial refinement, enabling them to provide far greater precision while keeping current with medical advances. All of these changes are driving increasing complexity in CI, emphasizing the pivotal role insurance medical directors must play in CI product design and pricing in order to ensure the product’s profitability and marketability. This article reviews the important considerations and challenges of which insurance company medical departments must be aware to ensure this product continues to be successful.

Critical Illness insurance is, in its essence, a simple product: it provides a lump sum payment to an insured upon diagnosis of a covered impairment as defined within the contract. The product, however, is not simple at all, and

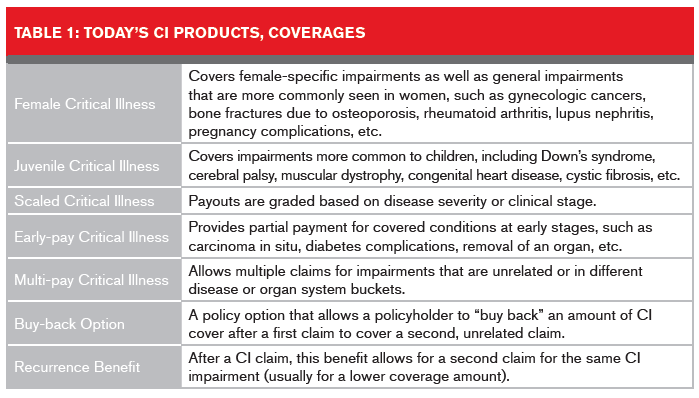

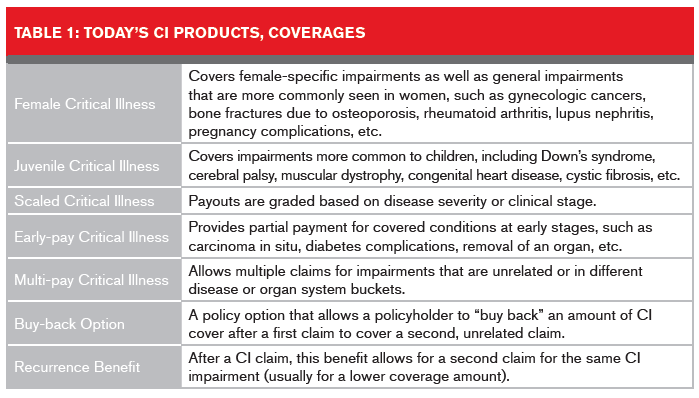

its complexities are growing fast. Currently, CI is available in several design configurations: policies specifically for juveniles and females; policies featuring scaling and partial payments; and multi-pay policies, with buckets enabling full payouts should the policyholder need to claim more than once. Policy options such as buy-back and recurrence benefits can also be purchased.

Impairments to Cover

In CI’s early days, only the so-called Big Four illnesses – heart attack, cancer, stroke, and coronary artery bypass surgery – were covered. Since then, the product and its features have evolved substantially. As Table 1 shows, CI products today come in a range of structures that can cover single and multiple impairment incidences.

The roster of impairments a CI product can cover has grown as well. Insurance companies today compete to provide the widest selection of illnesses, with some products now covering more than 175 diseases and conditions. Several products also incorporate “catchall” impairments, such as total and permanent disability (TPD), terminal illness, and loss of independent existence, which is adding further complexity.

When developing CI products, insurers need to determine which impairments are the most appropriate to cover, depending on the market to be served and its financial needs. The optimal number of covered impairments varies by market, but usually ranges from 13 to 23 conditions. Insurers also need to be able to underwrite the selected impairments effectively. It is best not to cover impairments that are difficult to clearly define with objective criteria or diseases open to potential negative impacts of medical advances.

The spirit of the product also needs to be maintained. CI definitions need exclusions and severity clauses in order not to cover non-critical conditions where financial loss to the insured upon diagnosis is minimal. For example, policies should not cover every type of burn, otherwise a sunburn would qualify. Also, not every abnormality incidentally found on a cranial CT scan should be covered, and CI carriers should not have to pay out for easily treatable minor cancers such as non-melanoma skin cancers that have good prognoses and do not generally result in significant financial loss to the insured.

As a general rule, for large-payout CI impairments, it is best to cover only serious, life-changing impairments that will shorten life expectancy, are expensive to treat, and commonly leave the insured with significant sequelae.

Drafting CI Definitions

Definitions in CI policies need clear, well-crafted, and unambiguous language to describe benefit triggers for each covered impairment in every country and market where it is offered. Language must also be legally defensible: a stray “and” or “or” could leave insurers vulnerable to litigation. Definitions also might be different for a Group CI product versus an Individual CI product. An example of this is in the definition of a progressive degenerative impairment such as Alzheimer’s disease. In an individual product, Alzheimer’s can be defined so that it pays out at a very advanced stage of the disease, whereas in a group product, it might be defined so that it pays out at a lower severity – a level when an insured’s capacity to work might first be impacted.

Also, if long-term guarantees on premium rates are used, wordings that offer more “future-proofing” would need to be incorporated into each CI definition.

It is also essential to not try to plug every hole in a CI definition. Doing so could make the product too complex for agents and the buying public to understand. CI definitions should have the following characteristics:

- Clarity in describing what is and what is not covered

- A match with the issuing insurance company’s pricing and marketing goals

- Close agreement, within reason, with existing clinical disease definitions

- Clearly written and objective claims triggers

- Resilience to and/or ability to accommodate to ongoing medical advances in order to maintain the spirit of the product.

In certain markets, model language for use by insurers in impairment definitions already exists. In the U.K., for example, CI impairment definitions are maintained and supported by the Association of British Insurers for utilization by all insurance companies. In other markets, insurers have developed their own definitional language, usually in tandem with a reinsurer or other product architect. There are pros and cons to adopting industry-wide CI definitions but again, medical directors play important roles in designing and updating these industry CI definitions.

Finding the right balance for these definitions, so language is clear, medically correct and understandable to claims adjudicators as well as to agents and policyholders, is best accomplished using a team approach, with representatives from the insurer’s medical, legal, claims, pricing and marketing divisions weighing in.

Impact of Medical Advances

The speed at which advances are taking place in medicine, from increased screenings, new biomarkers and diagnostics to new therapies and cures, is having a dramatic impact upon CI in terms of product design, pricing, and most of all, its definitions.

Certain CI definitions that demanded more invasive or antiquated diagnostic technologies have needed to be updated to meet current clinical practices, which use newer, less invasive diagnostic technologies such as genetic tests and recently discovered biomarkers. Also, changes in recent years to the clinical definitions of heart attack, cancer, stroke and Alzheimer’s due to new research developments have led to unexpected increases in claims experience in certain markets. For example, the incorporation of troponin test results into the clinical definition of heart attack has led to increased incidence of myocardial infarction diagnoses. In addition, new and less invasive surgical techniques such as cardiac keyhole surgeries and transvascular aortic and heart valve surgeries have led to necessary changes in CI definitions.

As new imaging and screening tests are discovered and developed, the potential to detect incidental impairments is increasing – impairments that may have no impact on the insured’s life and therefore might not warrant an approved claim. In addition, the rising worldwide trend of screening for various cancers – especially those affecting the breast, prostate and thyroid – are resulting in dramatic increases in incidence rates for these cancers, especially at the early stages. In Korea, for example, national thyroid cancer screenings resulted in a 15-fold increase in diagnosis from 1993 to 2011, without any change in thyroid cancer mortality.

Finally, new cures might mean that a once-critical condition might not be life-challenging in the future. For example, some types of cancers which once needed expensive bone marrow transplants can now be treated with less expensive oral medications.

The Medical Director’s Growing Role

Medical directors at insurance companies are playing increasingly important roles in the development of CI products. They assist actuaries to ensure the products are priced adequately and affordably. They work with product development teams to ensure the right impairments are covered and defined clearly in ways that will help mitigate the potential impact of future medical advances. They also contribute expertise in underwriting cases and claims adjudication.

With the newer scaled CI products, actuaries are needing medical director input regarding distribution of disease by stage or severity. Medical teams are being called upon to provide information for multi-pay products about the mortality associated with each covered illness and the inter-dependencies of various illnesses in combination. In addition, medical directors provide important input regarding incidence rate trends, the likely impact of medical advances, and the potential impact on a product's design of removing or altering a particular definition or exclusion, or reducing the waiting or survival period.

Currently, claims adjudicators at insurers that sell CI are seeing several areas of debate as well as claim challenges, where medical directors are providing important input. Some of these include the following:

- Malignant versus borderline or pre-malignant conditions surrounding carcinoids,

gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and bone marrow pathologies - The non-melanoma skin cancer CI exclusion and its impact on claims for cutaneous lymphoma and dermatofibroma sarcoma

- Claims for stroke, multiple sclerosis, head trauma and benign brain tumor where there are questions about permanent neurological deficits

- Whether incidental imaging findings coupled with certain symptoms constitute a valid CI claim for particular covered conditions

- Whether or not an acute Takotsubo cardiomyopathy diagnosis is claimable under the heart attack CI definition

- The validity of a CI claim for heart attack when certain diagnostic test results are missing

How these controversies are handled at claim time depends on the market, local legal precedent, and the definition used in the CI contract. The best team approach to these problematic claims involves the insurer, the reinsurer, and legal counsel (as appropriate).

Summary

Keeping CI products as simple and as marketable as possible is becoming increasingly essential. CI definitions must be well-worded with clear claims triggers and kept current with medical science.

Insurance medical directors play pivotal roles in CI product design and pricing to ensure the product’s sustainability and affordability. As long as all parties are aware of the impact of medical advances, CI can continue to develop profitably and serve an important public need.