In 1882, Thomas Edison, the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” introduced the U.S.’s first commercial electrical distribution plant.

Yet it wasn’t until 40 years later in the 1920s that electricity made a measurable impact on the nation’s economy. Why did it take so long? The problem wasn’t with electricity itself, but a lack of complementary technologies and ways of doing business: Factories needed to be redesigned to accommodate electricity and household appliances needed to be invented to expand electricity’s reach.

Insurance-linked wellness programs could be following a similar path. Years after such programs were first introduced, the right insurance technologies and business methodologies may now be in place to accelerate widespread adoption.

Making the Case for Wellness

Life insurance-linked wellness programs were first developed more than 20 years ago, and insurer interest in these programs has continued to grow ever since. Nevertheless, all these years and seemingly countless program launches later, the industry has yet to fully realize the potential of wellness initiatives. That may be beginning to change.

New and more insightful data sources, a better understanding of consumer behavior, continued advances in technology, and innovative approaches to incorporate biometric information into insurance offerings are changing perceptions. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic is leading many insurers to focus more on improved health and virtual solutions. As a result, wellness programs are increasingly viewed as promising vehicles for growth.

Wellness programs offer a range of win-win incentives:

- Insureds receive value beyond insurance protection with reduced premiums and better health outcomes; and

- insurers receive additional evidence to evaluate risk, a more engaged customer base, and improved health and longevity among policyholders.

Widespread adoption of insurance-linked wellness programs requires an understanding of the relationship between behaviors and health outcomes. We know that lifestyle choices such as inactivity and smoking significantly contribute to poor health and chronic conditions. We also know that insureds and insurers alike understand and appreciate the benefits wellness programs bring by incentivizing healthy behaviors. Quantifying the impact of these activities on mortality and morbidity provides an evidentiary foundation to advance and expand wellness programs in insurance.

Quantifying Lifestyle Behaviors

Physical activity is an essential component of wellness, and steps are a foundational measurement of activity in wellness programs. This is due to several factors:

- Steps are easy to measure;

- steps are an objective metric to compare activities; and

- steps provide a historical measure to evaluate activity, as steps were collected in early wearable devices such as pedometers.

Despite these advantages, steps are often an insufficient metric to gauge physical activity because not all activities are best quantified by number of steps. For example, steps may be an appropriate metric for a runner, but steps do not accurately capture the activity from other forms of exercise, such as swimming, cycling, or playing tennis.

Self-reported physical activity can eliminate some of the limitations inherent in measuring steps and provide additional insights into the impact of lifestyle behaviors on mortality. The study “Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer”1 compared self-reported activity to accelerometer data and found that both objective and subjective measures of physical activity produced qualitatively similar results. These findings demonstrate the relative reliability of self-reported data for studying the impact of activity on mortality experience. It is important to note, however, that survey participants such as those in this study are not incentivized to misrepresent self-reported activity data, and this would not be the case within an insurance application.

To understand the relationship between lifestyle and mortality, RGA analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), produced by the CDC, which is one of the United States’ largest in-person household health surveys. NHIS provides data for analyzing health trends and tracking progress toward achieving national health objectives and spans from 1957 to the present day; mortality linkage is available in surveys from 1986 through 2014. The modeled population from NHIS in this analysis consists of 754,726 survey respondents, including 102,851 deaths. Each modeled participant had a household income more than 2.5 times the poverty ratio, and all had an insurable interest.

Using NHIS data, RGA performed survival modeling to assess the impact of lifestyle behaviors on mortality in the U.S. population, controlling for age, sex, smoking, disease history, health status, and income.

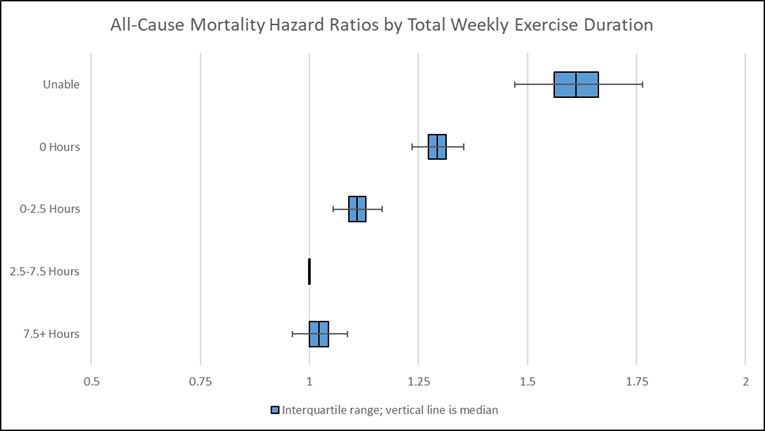

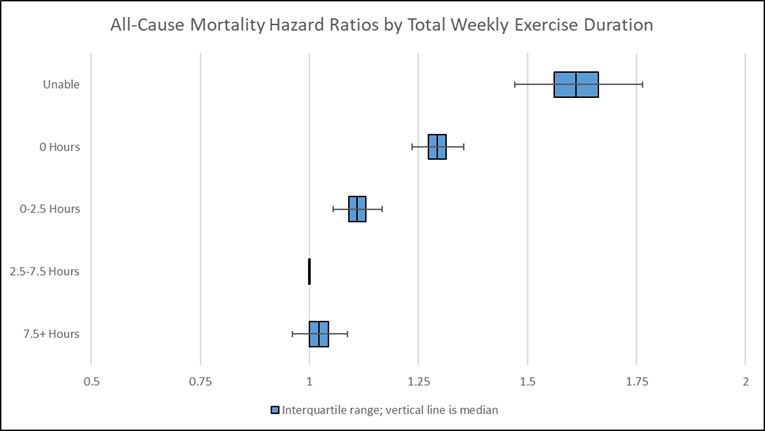

As Figure 1.1 demonstrates, those who do not exercise have far worse mortality experience than those who do. These results align with the guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which recommends at least 2.5 hours of exercise per week.

Figure 1.1:

Weekly Amount of Exercise

Source: RGA analysis of NHIS data, 1987-2014. Multivariate model adjusts for age, sex, smoking, disease history, health status, and income.

Notable findings from Figure 1.1:

- People unable to exercise have considerably worse mortality experience than those able to exercise.

- Among people able to exercise, those who chose not to have the worst experience.

Engagement in physical activity, particularly vigorous physical activity, becomes more important as we age. Numerous studies have concluded regular participation in activities, from moderate-intensity walking to very high-intensity sports, helps people maintain muscular strength and contributes to improvement in heart, lung, and circulatory system function. In contrast, less active lifestyles have been linked to premature onset of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, obesity, cognitive impairments, and general frailty in the elderly.2, 3

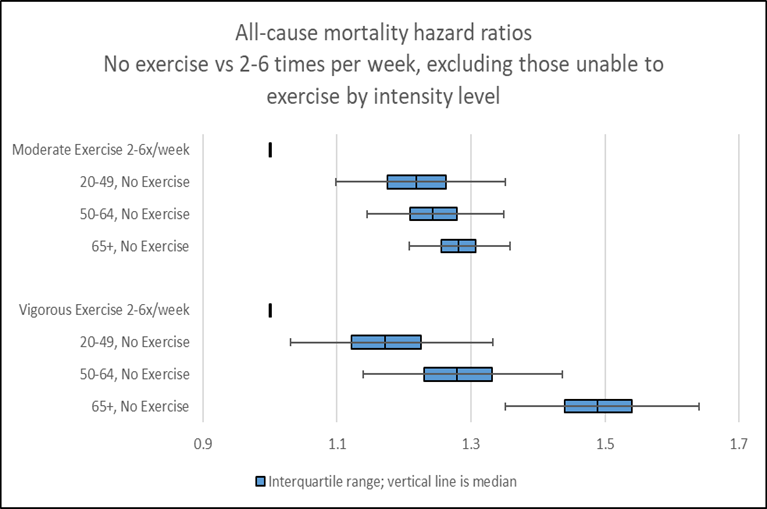

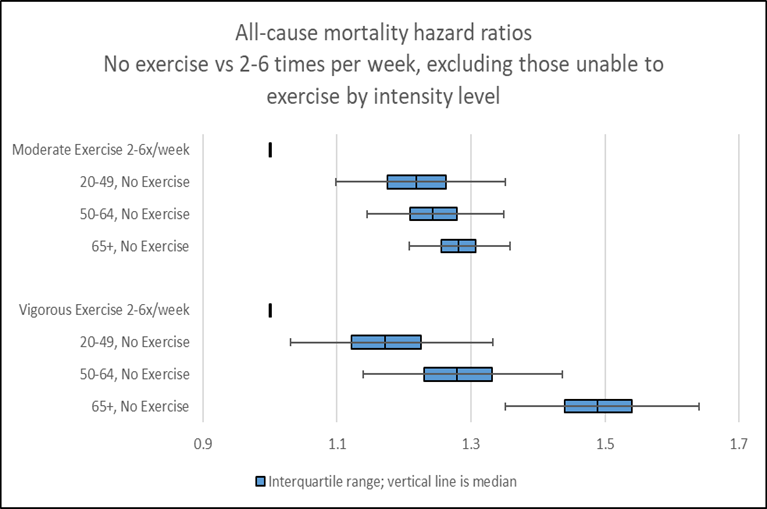

RGA studied NHIS data to more accurately quantify the impact of exercise intensity on mortality experience. Findings in Figure 1.2 demonstrate the mortality experience of members of different age groups who do not exercise relative to the mortality of members of those same age groups who exercise two to six times a week. The top set of bars compares moderate exercise by age, while the second set of bars compares vigorous exercise by age. Hazard ratios for those who do not exercise increase with age for both moderate and vigorous exercise intensity, indicating that physical activity is more important as we age.

Figure 1.2:

Exercise Intensity

Source: RGA analysis of NHIS data, 1987-2014. Multivariate model adjusts for age, sex, smoking, disease history, health status, and income.

Notable findings from Figure 1.2:

- Hazard ratios for those who do not exercise increase with age for both moderate and vigorous exercise intensity, indicating that physical activity is more important as we age.

- Ratios by age are more spread out in the second set of bars, implying that vigorous exercise is even more important than moderate activity at older ages.

To study the relative importance of smoking and physical activity on mortality experience, NHIS survey participants were grouped by both smoking status and physical activity. The measure of physical activity in this analysis was the perceived level of physical activity compared to people of the same age (peers). The top three bars in Figure 1.3 represent hazard ratios for people who have never smoked by self-reported activity relative to peers, the middle bars show experience of former smokers, and the bottom bars show the experience of current smokers. Every group’s result is set relative to people who never smoked and who consider themselves more active than their peers. While mortality experience improves with more activity, even the more physically active smokers experience worse mortality than less active non-smokers.

Source: RGA analysis of NHIS data, 1987-2014. Multivariate model adjusts for age, sex, disease history, health status, and income.

Notable findings from Figure 1.3:

- Regardless of activity level, mortality expectations for smokers are far worse.

- A physically active smoker has higher mortality experience than a less active never smoker.

Wellness programs typically include smoking cessation programs. While RGA’s data-driven analysis highlights the importance of exercise on longevity, the mortality implications of smoking far outweigh improvements from exercise.

Insurer Interest in Wellness Programs

The relationship between physical activity and mortality experience is clear, but how is the insurance industry using, or planning to use, wellness-enabling digital tools, services, and products to support healthy lifestyles among policyholders? How can these enabling tools and products help to motivate healthier lifestyles, prevent, and manage chronic conditions, and increase policyholder retention and consumer engagement?

RGA and RGAX surveyed 107 life and health insurers from around the world about their current plans, initiatives, challenges, and opportunities.

- 85 percent of respondents reported wellness as a top or moderate priority.

- 70 percent of respondents were creating insurance-linked wellness products.

- 57 percent of respondents currently offer wellness solutions, which they have launched to enhance brand loyalty, motivate positive behaviors, and reduce claims, among other reasons.

Nearly half of survey respondents believe that wellness programs must deliver an improved health impact. Two-thirds of respondents have pursued “wellness enablers,” a collection of digital platforms, tools, and apps designed to empower healthier living through information and engagement. Such results suggest that insurers’ focus is on improving overall health and well-being, not simply assessing risk.

In general, insurers see wellness as a vehicle to help drive innovation in a range of areas, including distribution, lead generation, and consumer engagement. Although wellness programs may have yet to achieve their full promise envisioned years ago, they are getting much closer, and new tools available today make these programs’ built-in shared incentives even more promising for accelerating future solutions. Figure 2.1 outlines the number of insurers (out of 107 surveyed) pursuing various wellness innovation initiatives and how these insurers intend to measure program success.

Figure 2.1:

Wellness Innovation

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased interest in wellness programs among insurers and insureds alike. Insurers have identified increased consumer interest in:

- Lifestyle management,

- virtual medical care,

- wellness-related apps and technology,

- virtual caregiver support,

- mental health support, and

- financial wellness.

With lockdown protocols and consumers’ discomfort with in-person contact limiting or even preventing insurers’ ability to conduct traditional fluid collection and paramedical exams, the pandemic has increased focus on digital underwriting evidence. To the extent that wearable devices can provide unobtrusive biometric data, these devices can be linked to wellness programs and contribute to a convenient digital sale. Although translating wellness data into actionable resources and practical underwriting evidence has proven challenging in the past, wellness initiatives are now finding success, and future applications could usher in a new era of consumer engagement with insurers and insureds coming together as long-term partners in health.

Conclusion

Insurers participating in RGA’s global wellness survey indicated they rely on biometric data, often combined with other external data, to inform the development of their wellness programs. Data-driven actuarial studies can help insurers quantify the mortality impact of wellness-related activity, and as the data available continues to grow, this will improve confidence in the findings and allow for further refinements in studies linking wellness program behaviors and mortality experience. Quantifying the impact of behavior on experience will enable wellness solutions that go well beyond those initiatives of the past often derided as mere marketing ploys and could help make wellness programs become a central component of the future of insurance.