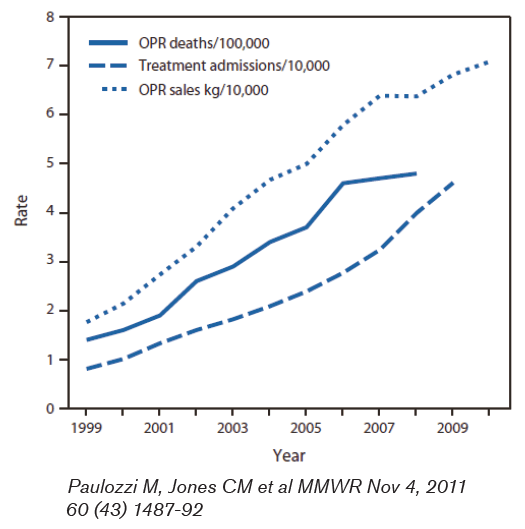

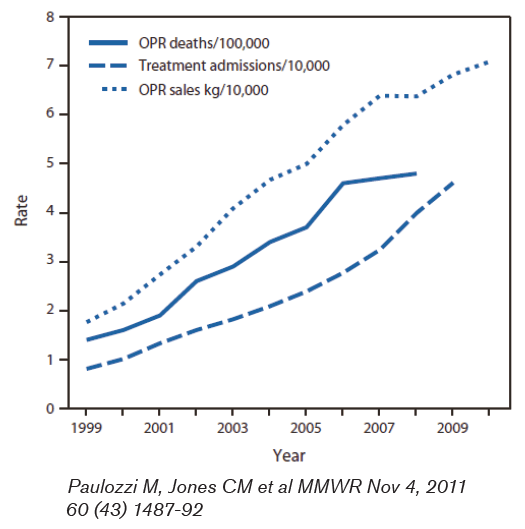

The number of prescriptions written for opioid pain relievers (OPR) has increased significantly in recent years.

Commensurately, the numbers of emergency department (ED) visits and deaths related to OPR have also increased. Sales of OPR in 2010 were four times what they were in 1999. By weight this amounted to 710 mg for every man, woman and child in the U.S. This amount could provide a typical dose of 5 mg of hydrocodone every 4 hours to every adult in the U.S. for an entire month.1

1.2 million ED visits in 2009 were for prescription drug problems, many of which were for OPR, which was double the rate in 2004. 4.8% of Americans age 12 or greater have used OPR non-medically.2 In a report of California Workers Compensation claims, 3% of physicians accounted for 62% of OPR prescriptions.3

Neonatal abstinence syndrome, a postnatal drug withdrawal syndrome caused by maternal opiate use, has almost tripled in incidence from 2000 to 2009 as measured by cases per hospital births per year.4

Deaths related to OPR totaled 14,800 in 2008 and this number has quadrupled since 1999 and now exceeds the number of deaths related to heroin and cocaine combined.1

Figure 1 illustrates these points.

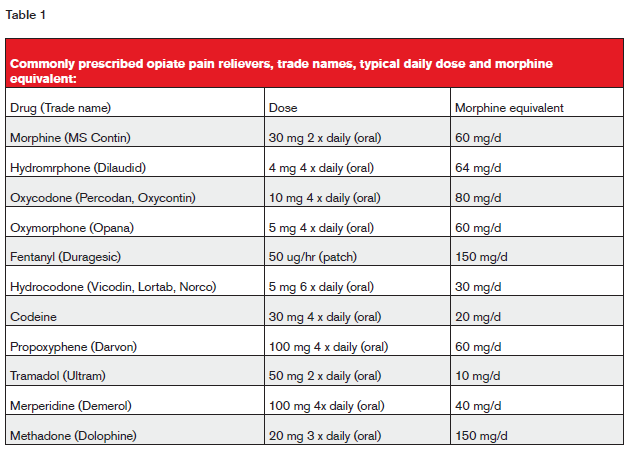

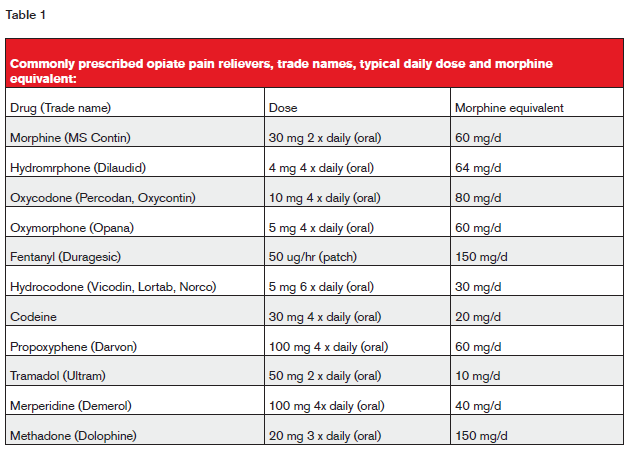

Commonly prescribed OPRs are listed in table 1 below.

Approach to underwriting

Prescribing physicians face a challenge in providing appropriate pain relief without causing long-term problems. Likewise, underwriters face a challenge in distinguishing appropriate from problematic OPR use. The approach to each proposed insured must be individualized and viewed in the entire context of the case. The typical requirements include attending physicians’ statements, financials, motor vehicle reports’ laboratory data and pharmacy database reports. From this information it is important to note if treatment is temporary or chronic, if there is any criticism or suggestion of abuse, if there are multiple prescribers or prescriptions or if there is concomitant use of other drugs or alcohol. Depression is common in individuals with chronic pain and any history of mood disorder and/or suicide attempts must be taken into account.

Pain management clinics and specialists are commonly seen involved in the care of these patients though data regarding their effect on mortality are lacking and it is likely any studies that would be forthcoming would have to take referral bias into account.

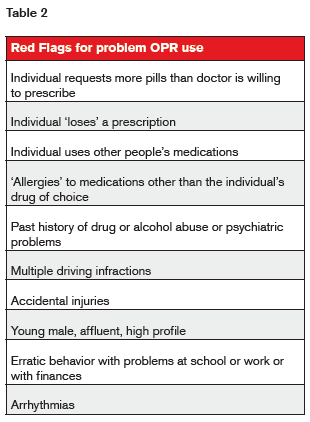

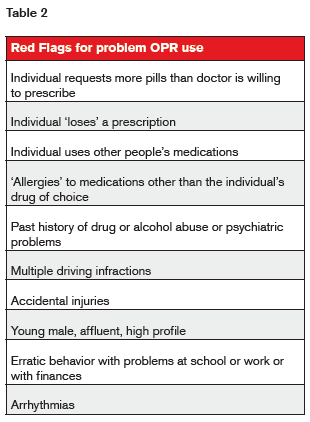

Numerous “red flags” for problem use have been noted and are listed in table 2.

Drug diversion for non-clinical purposes accounts for a substantial portion of deaths from overdose.2 While actual drug diversion for non-clinical use is sometimes difficult to identify in either a clinical or underwriting setting, the above information does lend insight, as do prescription database checks.

Prescription databases

Prescription database information is a useful adjunct to mortality risk assessment in OPR users. When available, this yields information regarding not only the OPR but other medications that might interact and potentiate OPR effects. It is not uncommon to see prescriptions for multiple different narcotics and the risk of overdose is increased in this context. Additionally, it is important to note the dose intensity, the pattern of prescription and the frequency of prescription fills, all of which correlate with mortality.

Dunn et al5 examined a cohort of patients in a large health maintenance organization in Washington state. They found mortality from opiate overdose increased with the amount of drug prescribed with a hazard ratio of over 3 for individuals prescribed a morphine equivalent of 50-100 mg per day and over 11 for individuals prescribed 100 mg or more per day.

Bohnert et al also reported a direct correlation between the maximum dose of opioid prescribed and death from overdose.6 They also found the highest rate of overdoses occurred in individuals with both scheduled and as-needed dosing regimens as opposed to either as-needed or regularly scheduled alone.

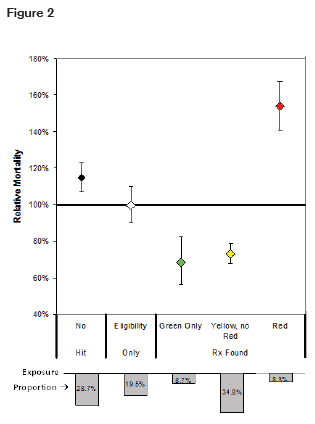

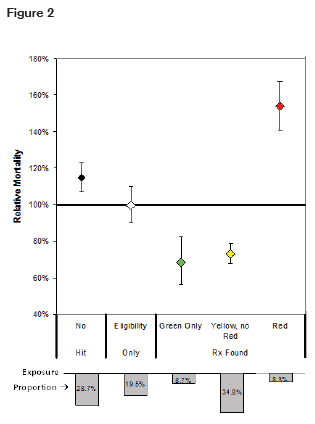

RGA has also conducted a study using prescription databases to predict mortality.7 Drugs were stratified into color-coded risk categories. Mortality was slightly elevated in the group of individuals who had no pharmacy data available, but significantly elevated in the high-risk or “red” group that included narcotics as well as other drugs. This is illustrated in figure 2.

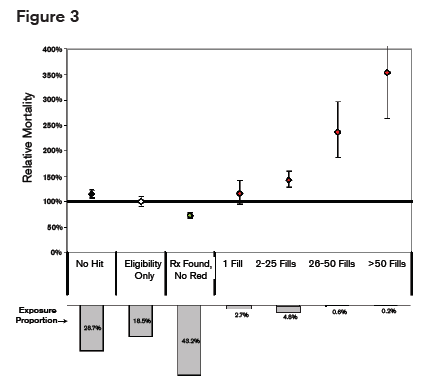

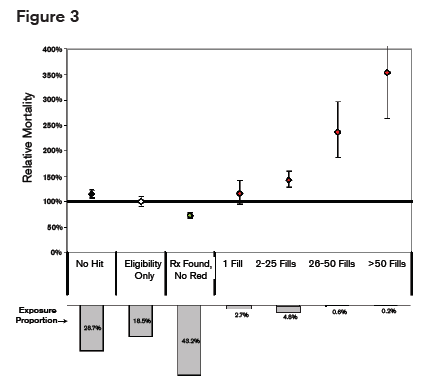

Mortality Mortality also correlated with the number of prescriptions filled as illustrated in figure 3.

It is therefore important when using prescription databases to note the dose, the pattern of dosing (scheduled, as-needed or both) and the total number of prescriptions, as these factors all correlate with death from overdose.

One potential limitation of prescription checks as obtained commonly in life underwriting settings is that they may not necessarily include prescriptions written by dentists. The vendor providing the information should be able to verify whether or not dental prescriptions are captured in the data they provide.

Summary

OPR abuse continues to increase rapidly associated with increasing deaths from overdose. Underwriting individuals on these medications is challenging and requires an individualized approach utilizing multiple sources of information as well as the entire context including other medications and alcohol use.

Prescription database information is useful in assessing mortality risk as deaths from overdoses correlate with the amount of OPR prescribed the pattern of prescription and the number of prescriptions.