Regulation and restriction of PFAS

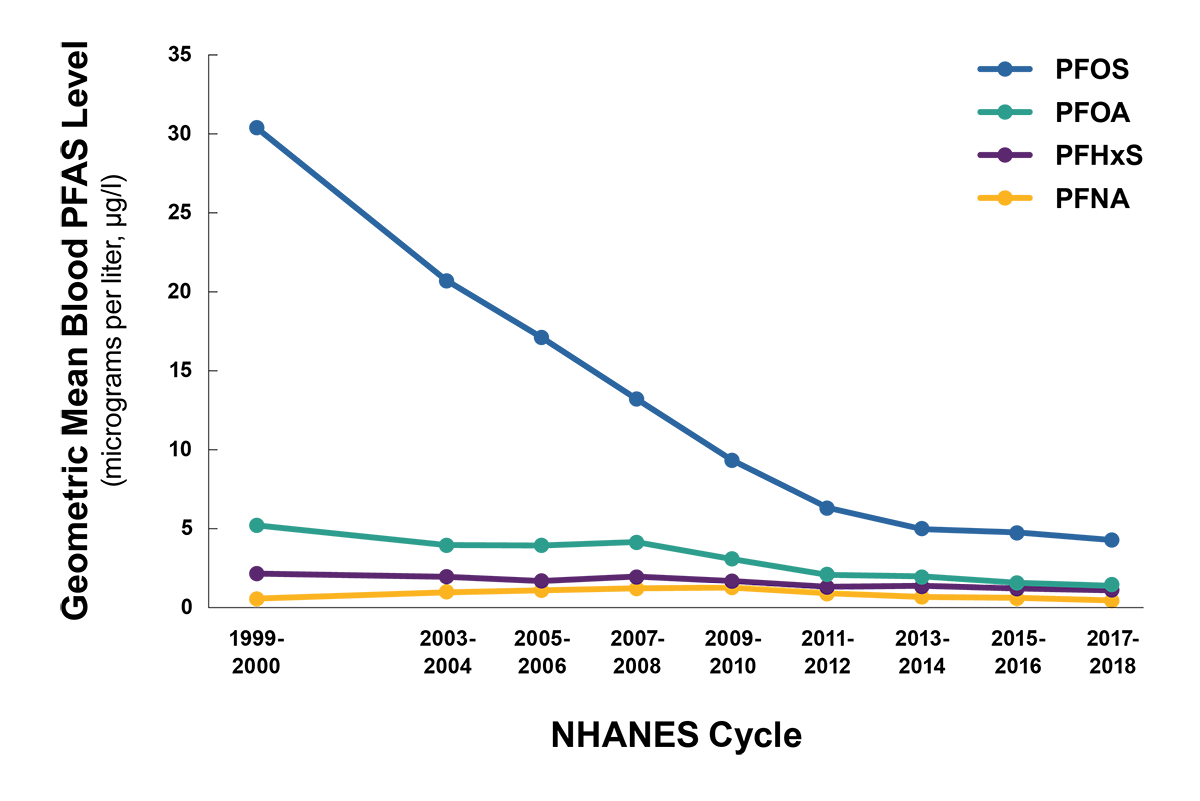

PFAS have been regulated and restricted in different ways around the world. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates PFAS, while the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) regulates PFAS in the European Union (EU). PFOS production was ceased in the U.S. in 2002 and PFOA was phased out in 2006.5 In February 2023, the ECHA proposed a significant ban on the production and use of PFAS in the EU.1 Under the EU Green Deal’s Chemical Strategy for Sustainability, it has been promised to phase out all non-essential uses of PFAS.16 In Asia, there are no regulations or restrictions on the use of PFAS, and it appears that much of the production of PFOS and PFOA has moved to this part of the world.5

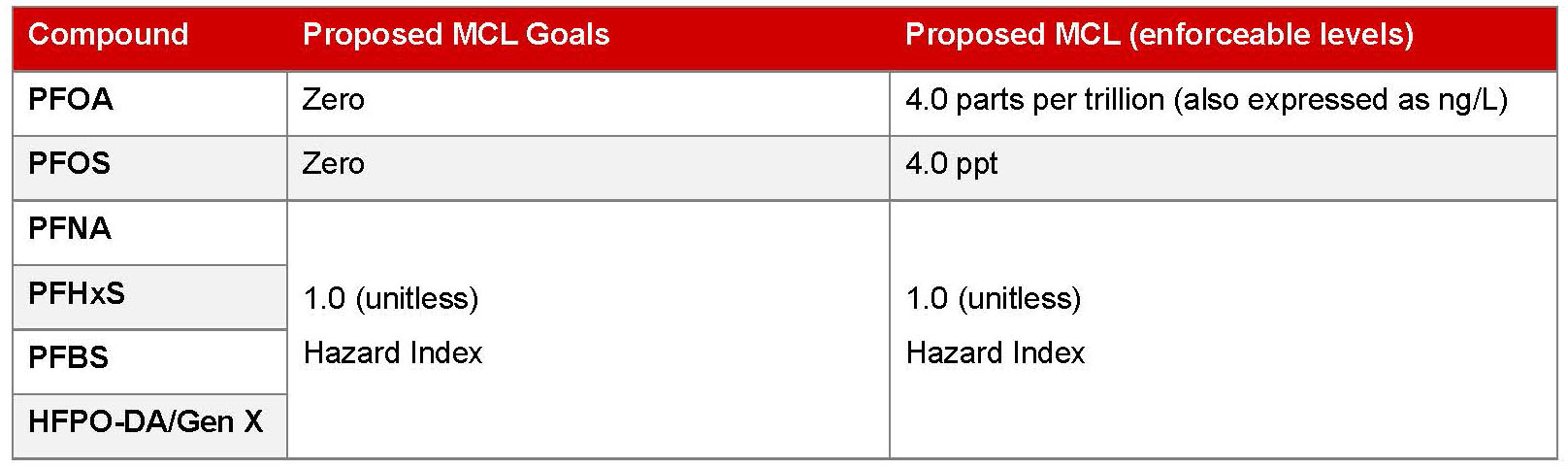

In March 2023, the EPA proposed maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for six PFAS in drinking water to help prevent thousands of deaths and serious PFAS-attributable illnesses. They include PFOA and PFOS as individual contaminants, and PFHxS, PFNA, PFBS, and HFPO-DA as a PFAS mixture. The EPA anticipates finalizing the regulation by the end of 2023.10

Table 1

Summary

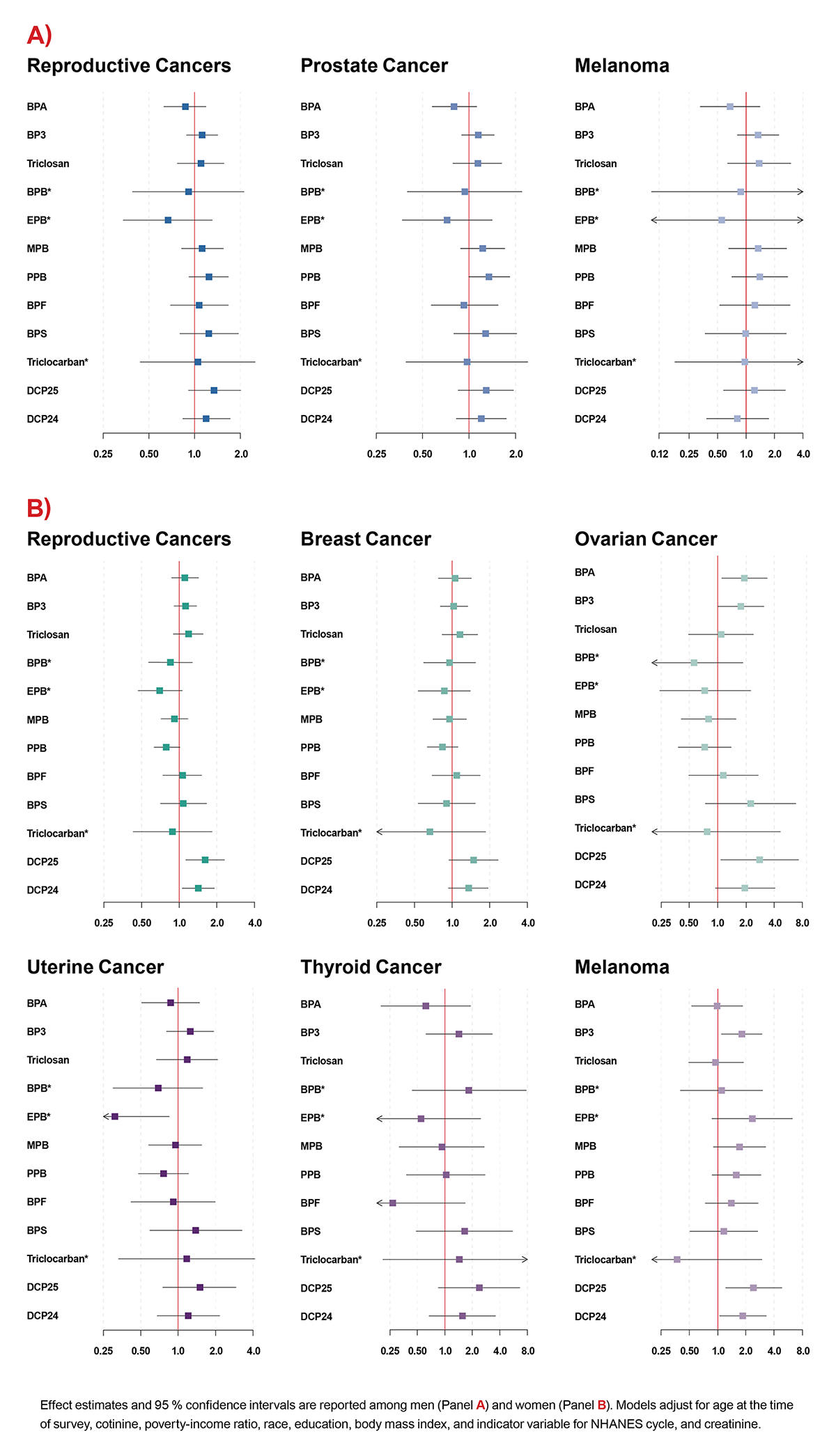

Although several PFAS have been banned or limited in their future use, they continue to have a lasting impact on the environment and human health, with detectable levels apparent in most individuals. While more research is needed, sufficient evidence shows a probable link between PFOA and high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular and kidney cancer, and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Insurers should be aware of the risks and impact of PFAS exposure and the increased risk of disease, particularly in occupational exposed individuals, and how these chemicals may affect human health in the years to come.