Globally, the insurance industry has spent quite a bit of time and energy building solutions designed to provide lump sums or income streams in order to help people who need to go into nursing homes.

These are the long-term care waters in which we insurers have long fished. We have built a myriad of plan types for this need: immediate needs annuities; whole-of-life plans with long-term care acceleration riders; standalone insurance plans and more.

However, is assisted care still the primary long-term need? Or have the health and care needs of older people evolved? What, indeed, are today’s needs and demands? Have our energies been misplaced, and do we need to refocus?

Before we start, I’d like to pose a question: How much do we really know about aging?

As a middle aged man, one thing that truly keeps me awake at night is worrying about my 80-year-old mum. No one teaches us what to expect from aging parents, and no one teaches our aging parents what to expect either; we are simply left to get on with it.

This lack of knowledge about the physical, social and psychological processes of aging continually leads to poor outcomes. For example, when my mum calls to tell me that she can’t cut her toenails any longer and can I help, that sounds innocuous right?

Wrong.

This is one of the classic signs that a person’s capabilities have declined to such an extent that help may be needed. The scenario below, compiled from quotes in several physicians’ statements, generally progresses like this:

“Once I can’t reach down to cut my toenails, I can no longer reach [down] to keep my feet clean. I start to develop fungal infections which I then can’t keep at bay and, as the health of my feet declines, I start to change the way I walk to compensate for the sore areas I have developed. As I change the way I walk, I become more unsteady and eventually I have a fall. As an 80-year-old my bones are [only] 70% as strong as a 50-year-old’s1, so my chance of a fracture is significantly raised. Once I’ve fallen once, I’ll fall again and again and again.”

Any intervention at this early stage of advancing frailty might not halt my mum’s decline, but it may help manage her risk factors, and it would definitely help her maintain a healthy, active and fulfilled life for a longer time.

The two things that strike me about this scenario are first, the blinding simplicity of some of the lead indicators of increasing frailty, and second, the lack of awareness of what those indicators actually are—not only for older persons, but also for their well-educated, middle-aged middle income children.

Gone Fishing

Historically, long-term care insurance products have been designed to deal with the costs and typical durations associated with the care (nursing) home element of the last years of life. In Britain, these costs are approximately £39,5002 per annum if nursing care is required, and mean stays of all residents before death are 2.5 years.3 In the U.S., nursing home costs average $92,000 per annum.4

The scale and global nature of this issue means the waters we are prospecting are vast. In 2015, 48 million Americans were over age 655 but there was also 137 million Chinese over age 65.6 As the impact of China’s one-child policy (which did not conclude until early 2016) continues to filter through its population, it will create a unique set of additional tensions for the Chinese.

Despite the obvious need for final years care, in the last five years we have seen the U.S. long-term care insurance market collapse. Companies such as John Hancock have pulled out as they struggle with a legacy of past pricing7, and Genworth sold itself to a Chinese buyer to re-capitalize following $2.5 billion of legacy LTC losses.8 What undid the U.S. market has been the product structures, which did not allow companies to respond to the risks chronic older-age conditions such as dementia presented as sufferers started to survive well beyond original expectations.

The lack of long-term certainty around governmental social care policies in the U.K. and elsewhere, has also created a vacuum into which insurers are unwilling to step. Without governments assuming long-term care’s tail risk, it is hard to see insurers rushing to stimulate markets.

Claims triggers that support LTCI have traditionally been designed only for the final years of life. Typically there are six Activities of Daily Living (ADL)-based definitions, with policyholders having to fail two or three in order for a claim to be accepted. Examples of ADLs language from current policies includes:

- Feeding yourself—the ability to feed yourself when food has been prepared and made available.

- Maintaining personal hygiene—the ability to maintain a satisfactory level of personal hygiene by using the toilet or otherwise managing bowel and bladder function.7

Usually policy language around claims triggers also includes a separate mental health definition. For example:

Irreversible mental incapacity due to an organic brain disease or brain injury supported by evidence of progressive loss of ability to:

- remember;

- reason; and

- perceive, understand, express and give effect to ideas; which causes a significant reduction in mental and social functioning, requiring the continuous supervision of the person covered.

In all cases, those who satisfy these criteria must be in a bad way indeed. It is also worth thinking about the real environment and the social stigma associated with U.K. care homes which was summed up by my wife’s great aunt who, despite crippling frailty, was determined not to be moved to a care home. Being a forthright Yorkshire woman, her reasoning was simple, if not politically correct: “They are full of mental people, and I’m not mental.” The unfortunate reality is, 80 percent of U.K. care home residents suffer from dementia or some other form of serious cognitive impairment.9 For the 20 percent of sane but frail residents, this must be a difficult environment in which to spend one’s final years.

It is useful to also think about some of the behavioral biases at play here: people in the U.K., for example, know that one in four will likely need this kind of care support, but no one thinks it will be them. And in the U.S., the figure is one in three. Sobering, to say the least.

Nothing here makes long-term care as we know it an appealing customer prospect. No one I know is looking forward to not being able to dress or feed themselves, and no one is actively looking forward to dementia. It makes LTC, perhaps, the ultimate grudge purchase.

Should We Find a new Place to Fish?

Talk to older people, and they will tell you what they want: they want to grow old in their own homes, surrounded by their special possessions, their memories, and the community they know well, where they have friends, social ties and relation-ships. They want to feel safe, supported and socially valuable. They want to be independent for as long as they can. Look at your own life: isn’t this what you want for your own parents and, ultimately, for yourself? Shouldn’t we insurers therefore be building products that allow people to do just that for as long as possible? It’s a much more positive sales message, but it will require some distinctly different thinking.

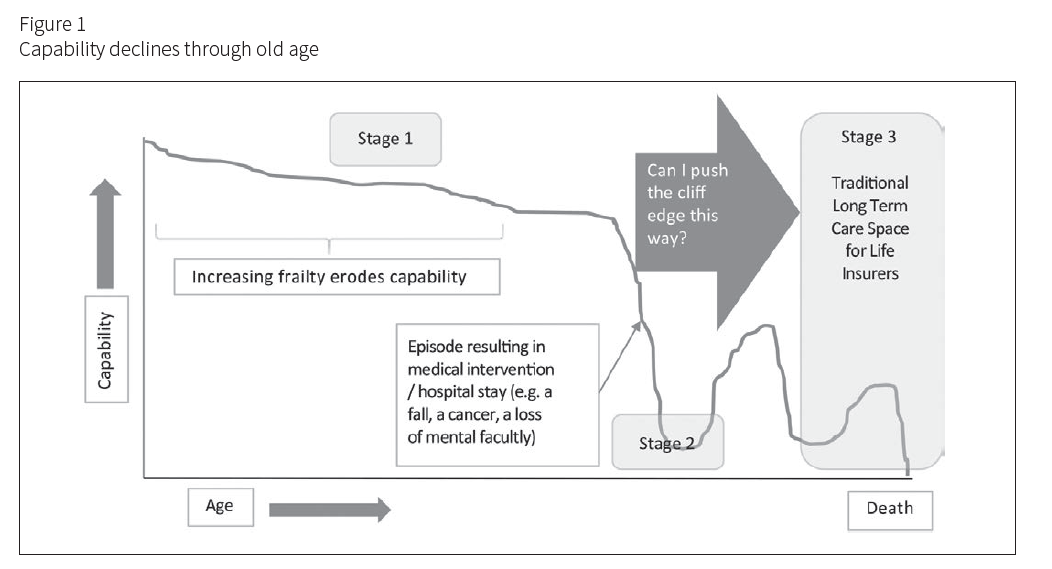

After age 65, people’s physical and frequently mental capabilities inexorably decline until they die. Figure 1 tracks a path many will experience. Stage 1 shows capabilities declining as they age until an event occurs that moves them to Stage 2, during which capabilities decline sharply. Stage 2 could be triggered by a fall, illness, loss of a spouse, or a sudden reduction in mental capacity. At this point, most national health systems will kick in, providing critical care in an attempt to preserve life and return the patient home. Once in the health system, patients will start to gain access to different levels of recovery services, but their capabilities are unlikely to return to their original levels.

Looking again at Figure 1, much of the energy insurance com-panies have expended has been in providing help and cover for the final stage of life (Stage 3), while little energy has been expended on understanding the pre-collapse of capability stage (Stage 1) and finding supportive, insured structures to push back the cliff edge of the capability decline into Stage 2.

Now consider consumer demand. Everyone wants to live happily and healthily in their own homes for as long as possible. Would a proposition designed to push back the point of capability collapse prove attractive? And what would we need to get there?

First it would require a new set of claims triggers. Today’s ADLs are too severe for earlier stages. It would also require new thinking around the measurement of frailty, which is all too often physically based, when we know the impact of social connection and loneliness can also be severe for longevity. (A 2015 study published by the Association for Psychological Science found that chronic loneliness can be as detrimental for longevity as a 15-cigarette-a-day habit.9)

The concept of IADLs (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) has been around since the late 1960s. Tools such as the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale10 provide a useful way to classify how people cope with day-to-day tasks such as laundry or shopping. These tools also help show when early interventions might be beneficial, but take no account of the complex picture of what really happens in the lives of older people.

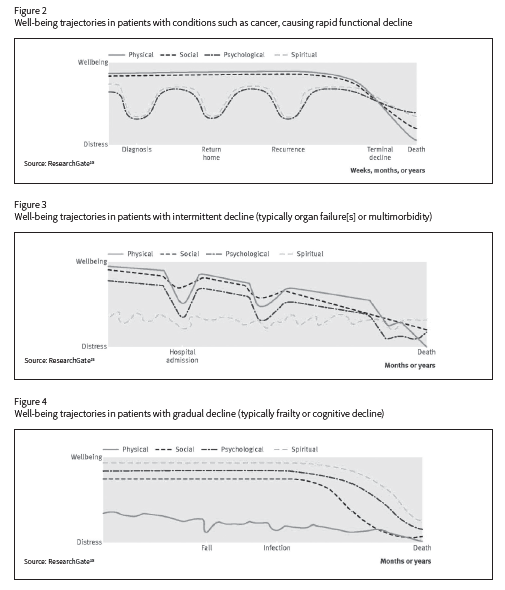

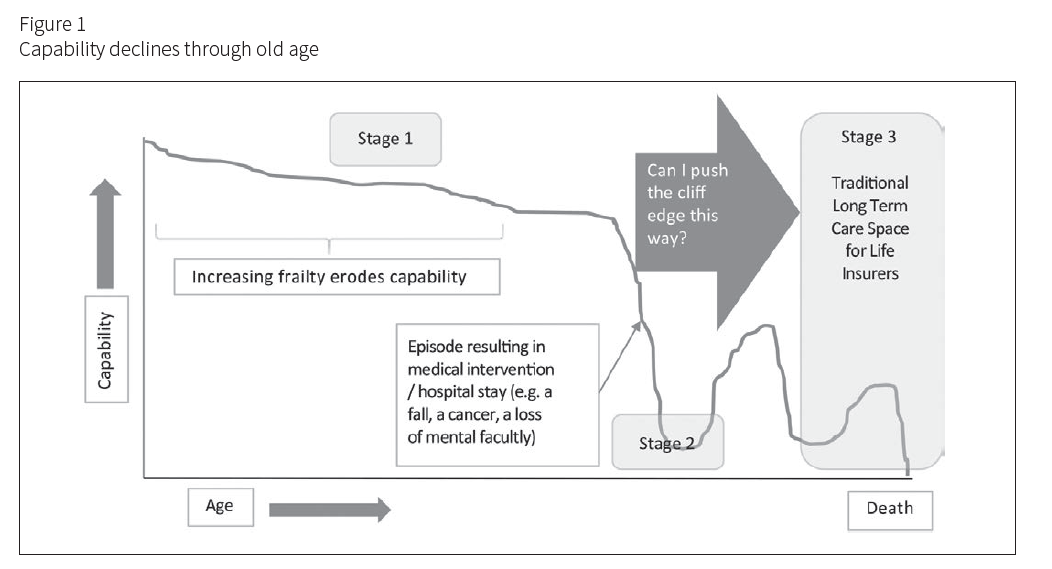

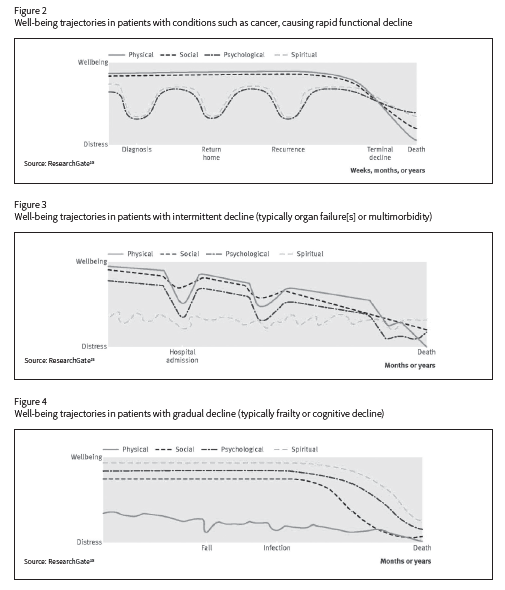

Scott Murray, Professor of Palliative Care at Edinburgh University in Scotland, has been using a four-dimensional model which looks at the physical, psychological, social and spiritual journey toward death. His well-being trajectories are drawn from the experiences of a large qualitative study group which was tracked through to death.11

Here we see the deep stresses experienced by cancer sufferers due to episodes such as diagnosis and recurrence, whereas the cancer itself often causes only a gradual decline in physical and social capability.

The physical decline from sudden organ failure can be sharp and will trigger psychological lows, and often generates associated drops in social interactions. Spiritual distress is likely to be a function of a person’s inner resilience and will fluctuate more over time.

The very gradual physical decline of frailty for people usually reaches a tipping point, at which life for them seems to start to lose meaning. Death is often preceded by warning signals such as a decline in social interaction, closely followed by psychological collapse and existential distress (i.e., knowing that it’s time).

The interlinked nature of these four aspects—physical, social, psychological, spiritual—has begun to be built into modern frailty scores such as the recently developed Electronic Frailty Index12 (eFI). These scoring systems start to take account of both the physical and social elements of aging and are a useful step forward from previous frailty scores, which typically concentrated only on purely physical aspects such as grip strength, or measuring the time it takes to get up from a chair, walk a few paces and sit back down.

The challenge we face as an industry is to use these kinds of learnings to create new benefit trigger points for our products. This can open up a market for frailty care products that can be designed to help support people living at home for as long as possible.

Catch of the Day

Insurance should be about creating socially useful outcomes at a time of great need for the individual. As our aging and increasingly frail populations expand and continue to want to live at home, we need to rise to the challenge by thinking imaginatively about long-term care claims triggers and the ways in which we would monitor and measure when claims occur.

We also need to think carefully about how to make claim benefits truly useful, because we know that most of our customers lack the skills and knowledge to understand the problems associated with frailty and to act in an appropriate way. The successful life insurers of tomorrow will have to provide benefits and service wrap-arounds to guide claimants and their families to the best outcomes.