Most people have a problem life insurance can solve: If your family would struggle to survive the permanent loss of your salary, then life insurance could be vital. This is the case for hundreds of millions of people around the world.

The challenge is that most people do not realize they have this problem.

Few people spend time thinking about the consequences of low-probability events and are therefore disinclined to consider the need for life insurance. This has given rise to the industry adage: Life insurance is sold, not bought.

But surely, the COVID-19 pandemic has awakened public awareness of the need for life insurance, right? With the world shut down and media reports filled with stories of tragic loss of life, people are increasingly aware that good health and a long life are not givens they can take for granted.

Initial media reports spoke of COVID-19 fears leading to increased online life insurance sales, with Forbes magazine even reporting evidence of “panic shopping”. At RGA, we have been actively analyzing available data to identify and try to explain any early patterns.

Early data indicates limited early impact

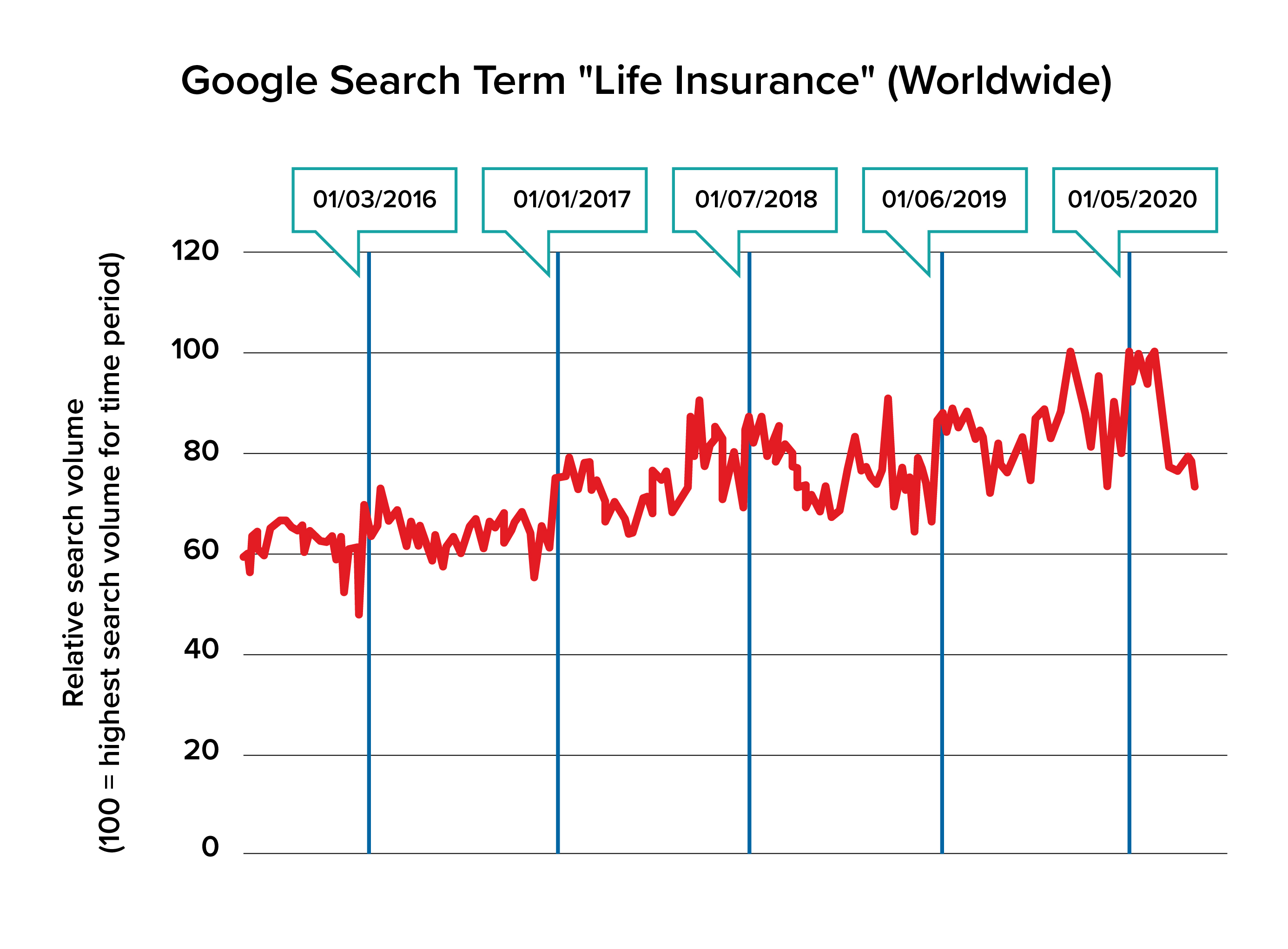

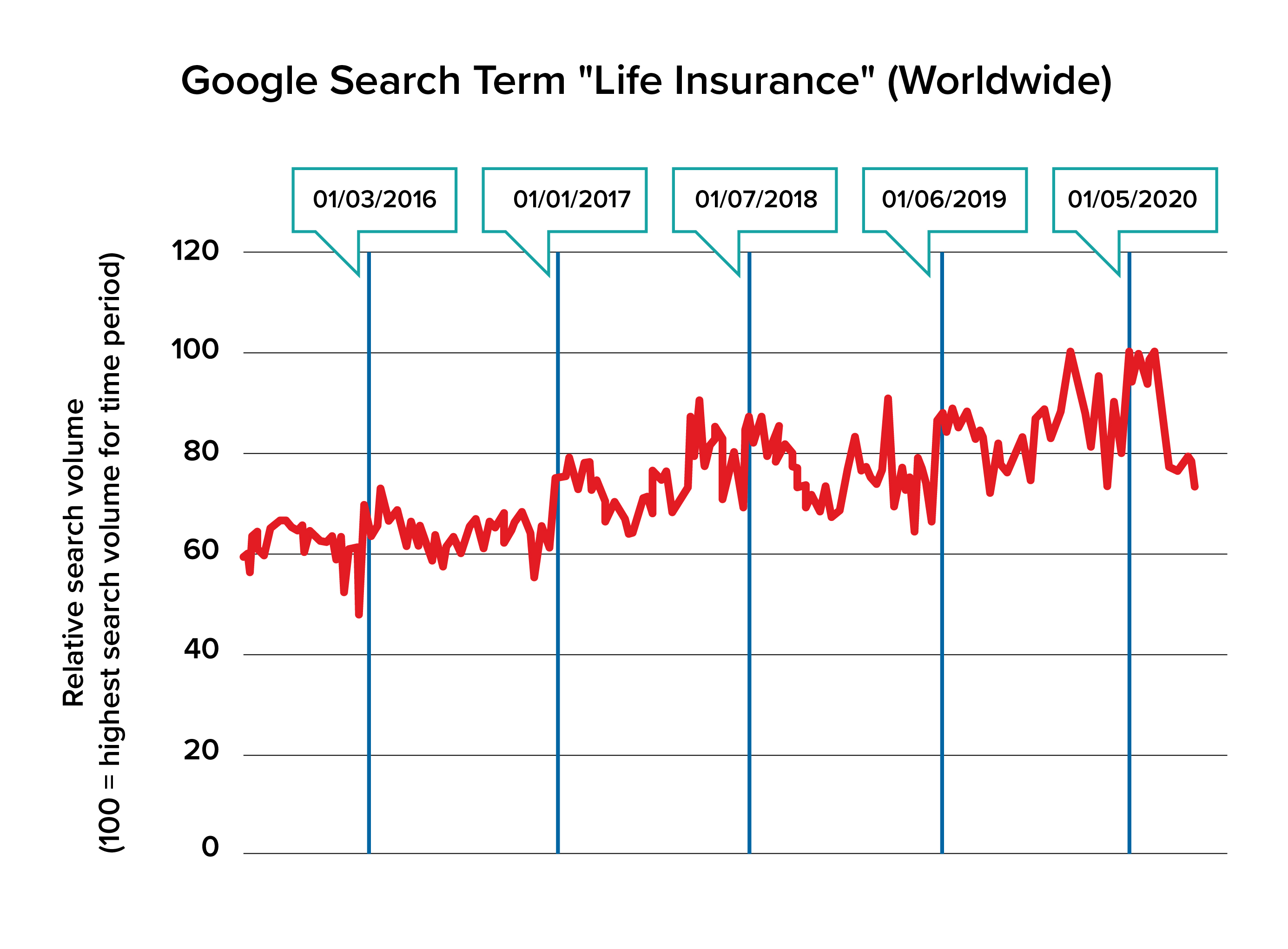

We began with Google Trends data to determine how searches for life insurance have been affected.

Source: Google

The chart covers the period May 3, 2015 to April 26, 2020. The data is based on random sample of searches, excluding duplicates by user. Results are relative to all other Google searches during that period and geography – decreases are relative to other searches, not necessarily absolute. 100 = highest relative search volume for that term

As the graph above shows, worldwide searches for “life insurance” have risen steadily over the last five years and reached a peak from January to early March 2020, coinciding with the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak. However, they have since fallen back to pre-virus levels. Furthermore, this peak did not occur in all countries. Analysis at a country level shows that the U.K. and U.S. mirror, and perhaps drive, the global pattern, but no discernible peaks or subsequent decreases coincide with COVID-19 outbreaks in Italy, China, Germany, Australia, India, or South Africa.

We should be cautious about drawing too many conclusions from Google Trends data. Considerable noise and fluctuations make it difficult to distinguish clear effects from statistical randomness or other patterns. For example, similar Q1 trends occur in the previous four years – although the March 2020 decrease is much larger than in these years. Most importantly, Google Trends does not indicate causation. For example, some people may have been searching simply to check if their life insurance policy likely covered COVID-19.

Yet evidence from other sources supports the U.S. Google Trends pattern. A LIMRA survey of 47 U.S. insurers assessed the impact of COVID-19 on individual life sales and applications in the U.S. 24% of companies reported that online and mobile applications rose in March, but 63% reported either no change or a decline. Only 7% saw an increase in face-to-face applications and 9% an increase in call center or mail applications. Nearly half of companies said they were expecting a decline in sales in March, with 20% expecting a decrease of 10% or more. How this reflects normal seasonal fluctuations is unclear, but most companies were expecting sales in the full first quarter to be flat at best.

According to the MIB Life Index, which measures U.S. life insurance application activity, demand for policies in January and February reached its highest level since 2015 but then dropped by 6.7% in March and a further 5.5% in April. This was a year-on-year fall of 2.2% in March and 3% in April.

Data available to date suggests that even if an initial COVID-19-related bump in applications occurred in some markets, that bump was both limited in time and geographic spread and may be outweighed by a subsequent dip in applications. So we must now ask: Why has COVID-19 had such a seemingly limited impact?

Life insurance is still sold, not bought

It is possible that any initial rise in searches and applications came from those already considering life insurance and for whom COVID-19 acted as a final spur and accelerant. Some media reports support this thesis. This could also explain why the sales impact was greatest in those markets where it is easy to buy life insurance online or where consumers are accustomed to buying other financial products online. Similarly, advisors may have accelerated sales ahead of the lockdown, as they anticipated delays and restrictions on medicals, lab tests, and other underwriting requirements. The subsequent reduction could also then reflect the delays and restrictions that people experienced once the lockdown began.

For the majority of those people not already considering life insurance, data indicates the pandemic has not motivated them to make a purchase. Also, the subsequent drop in searches does not suggest consumers are trying to buy online but finding it difficult to do so. The key reason, of course, may be economic. Most people do not view life insurance as an absolute essential, so if the primary breadwinner has lost, or is at risk of losing, his/her job, it is unlikely they will decide now is the time to spend what little money they may have on life insurance.

This is another reason why, counterintuitively, now might be a bad time to be promoting life insurance. It is easy to forget many people have an instinctive negative reaction to talking about money in relation to death. We are hearing about an increase in complaints and negative comments in response to online ads for life insurance, even when they are seemingly innocuous and make no reference to COVID-19. One prominent clergyman in the U.K. has even criticized the “grim promotion” of life insurance ads on Twitter. Many insurers have recognized this and are delaying planned email marketing pushes.

It may also be that the risk of COVID-19 is still too abstract for most people. One of the main triggers for purchasing life insurance occurs when someone we know passes away, especially if that individual is young and leaves behind a family. This was highlighted earlier in 2020 with the death of basketball legend Kobe Bryant. The volume of life insurance application requests and submissions spiked by over 50% in the days after the 41-year-old’s death on January 26, before returning to normal levels within a week, according to True Blue Life Insurance, an online aggregator and comparison site for life insurance. True Blue’s CEO commented: “In a lot of the phone calls to our agents, Kobe came up.”

Whereas a personal story of loss such as Kobe Bryant’s can significantly impact numbers and statistics, the risk of COVID-19 may still feel distant and theoretical for many people.

Or perhaps this crisis is just another reminder that the life insurance industry has not yet cracked the digital distribution challenge. Buying life insurance is not natural human behavior. In fact, from a behavioral science perspective, it is probably one of the hardest products to sell. We are drawn to personal, immediate, and certain rewards – but the rewards of life insurance are for others, seem distant, and often appear uncertain.

People need to be persuaded to buy life insurance and the human-to-human approach remains the most effective. Even if we see an increase in online applications, it may not make up for losses incurred from sales teams’ inability to go out and sell. For example, Ping An in China has reported a hit to sales driven by a decline in face-to-face services.

An uncertain future

It may be that COVID-19 will eventually help drive demand for life insurance, but not quite yet. As lockdowns began and people were stuck at home, often juggling work and parental responsibilities, life may have simply become too busy to think about life insurance, especially as many came to grips with social distancing and other disruptive public health measures. We are still in the eye of the pandemic storm, and people have more immediate concerns than life insurance.

COVID-19 could create fertile ground for future sales opportunities. It has been suggested that younger generations, especially in developed markets, view life insurance as less necessary than previous generations did at the same age.

This may change in a world where illness or accident is no longer a distant threat. Once the immediate COVID-19 fear has passed, insurers may find it easier to help consumers appreciate the “peace of mind” life insurance brings.

It is clearly too early to draw conclusions about how COVID-19 will change society and undoubtedly too early to be certain how it will affect demand for life insurance. However, at the moment, the evidence suggests that the adage about life insurance being sold, not bought still rings true. COVID-19 is hampering the intermediary sales channel more than at any time in living memory. For many developed markets, this merely highlights a problem expected to occur in the next few years anyway as the intermediary market continues to age and shrink.

In recent years, the life insurance industry worldwide has made great strides in making life insurance easier to buy. The focus may now need to shift towards finding ways to make it easier to sell.