Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GISTs) can occur anywhere along the GI tract but are most commonly found in the stomach (60% to 70%), and occur less frequently in the small intestine (20% to 30%), colon and rectum (5%), and esophagus (<5%). Rarely, GISTs can occur in the omentum, mesentery and peritoneum.

Malignant GIST tumors represent less than 1% of GI cancers. Hematogenous metastases from GIST most commonly involve the liver, omentum, and peritoneal cavity.

Global GISTs incidence is relatively rare at between 7 - 20 per million, although true frequency is unknown. Incidentally found microscopic GIST tumors can be more common. Small GIST tumors have been co-incidentally found in 35% of patients when their stomach was removed due to underlying gastric adenocarcinoma. With increased screening and use of imaging techniques, it is expected that we will see a further increase in GIST tumor incidence rates in the future.

The mean age of diagnosis is 63 years old. These tumours appear relatively rarely in individuals under 40 years of age. Most GISTs are sporadic but some are familial, due to inherited mutations in the KIT gene, and some will appear in patients with neurofibromatosis. The majority of patients with gastric or small bowel GISTs present with GI bleeding, anemia, or abdominal pain. These tumours can also be found incidentally when investigating a patient for some other gastrointestinal disease or on routine imaging of the GI tract.

These GISTs originate within the wall of the stomach or bowel and can grow into or away from the GI tract lumen. This means that simple endoscopy can miss these tumors or underestimate their size. Endoscopic ultrasound better estimates the size of these tumors. In terms of staging, 53% of GIST tumours stage as localized, 19% as regional, 23% as distant, and 5% as unstaged. These tumours are staged by the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th Edition Cancer Staging manual as Stage I to IV based on:

- Tumour size;

- Number of mitoses seen per 50 high-powered fields (HPF) or the so-called “Mitotic Index”.

GIST tumors have also been stratified by risk into four levels, tagged I to IV, also based on tumor size and mitotic index. The designations are: “very low risk”; “low risk”; “intermediate risk”; and “high risk”.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumour a GIST?

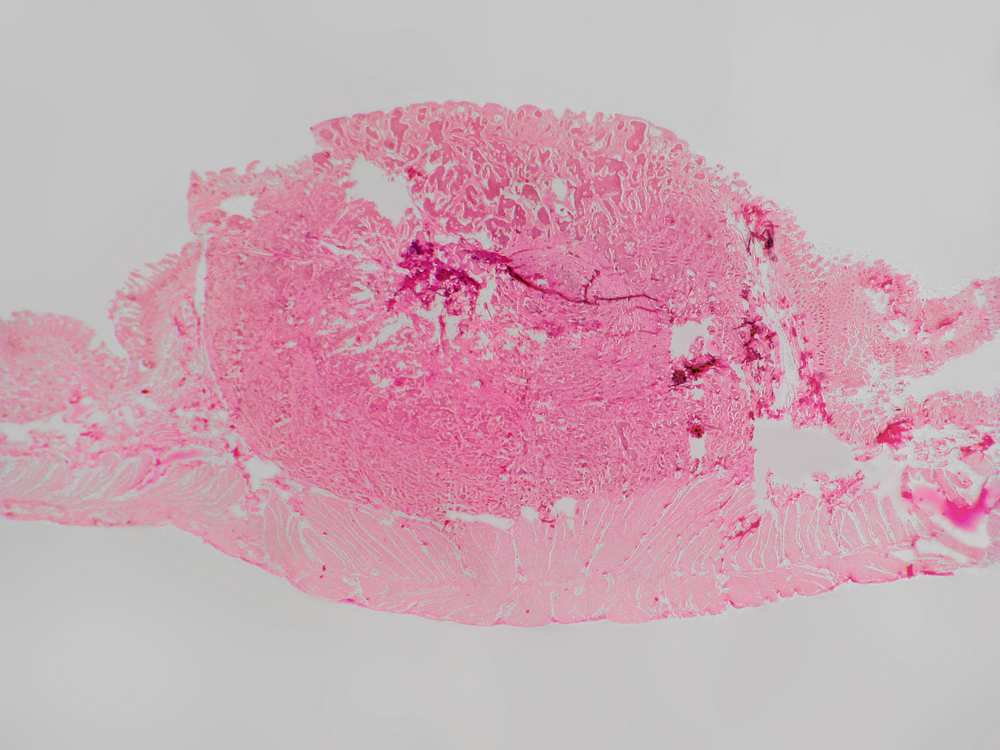

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%), epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than 90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to two- thirds of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately 10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3), respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication challenging. The majority of GIST tumours were previously thought to be benign due to their characteristically bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as “benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as benign or borderline. There is some debate that non- gastric GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5 cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

- Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

- Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

- Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site, that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields (mitotic index)

- Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

- Check their company’s critical illness definition to ensure GISTs are not excluded.

- Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was based on both pathological examination of the surgically removed tumor and appropriate immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where available).

- Review the pathology report of the resected tumour to assess size and mitotic index along with tumour location.

- Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

- Consult your medical adviser where you have any doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your policy has been satisfied. G CV

References

1. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Human Pathology 2002 May;33(5):459-65 and Int J Surg Pathol. 2002 Apr;10(2):81-9.

2. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, Hsiung CY, Lu D. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007 Jun;141(6):748-56.

3. Jung ES, Kang YK, Cho MY, Kim JM, Lee WA, Lee HE, Park S, Sohn JH, Jin SY. Update on the proposal for creating a guideline for cancer registration of the gastrointestinal tumors (I-2). The Korean Journal of Pathology 2012 Oct;46(5):443-53.

4. George D Demetri, MD, Jeffrey Morgan, MD, Chandrajit P Raut, MD, MSc, FACS Epidemiology, classification, clinical presentation, prognostic features, and diagnostic work-up of gastrointestinal mesenchymal neoplasms including GISThttp://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-classification-clinical-presentation-prognostic-features-and-diagnostic-work-up-of- gastrointestinal-mesenchymal-neoplasms-including-gist?source=search_result&search=GIST&selectedTitle=1%7E70

Literature review current through: Dec 2014. This topic last updated: Nov 18, 2014.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumour

a GIST?

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls

into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%),

epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with

spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate

compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising

in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other

benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy

alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in

the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true

leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be

difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably

or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the

molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of

GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and

immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them

from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were

inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous

collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than

90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of

the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from

other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other

spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another

tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT

mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived

growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to twothirds

of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately

10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene

or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST

malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their

pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and

have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and

metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or

malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3),

respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication

challenging. The majority of GIST tumours were previously

8

G L O B A L C L A I M S V I E W S w w w . r g a r e . c o m

thought to be benign due to their characteristically

bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming

increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have

the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics

state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as

“benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as

benign or borderline. There is some debate that nongastric

GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are

between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would

be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as

malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5

cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be

labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant

tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific

reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following

claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to

consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

• Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

• Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

• Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site,

that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields

(mitotic index).

• Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree

of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or

distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated

with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or

chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

• Check their company’s critical illness definition to

ensure GISTs are not excluded.

• Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was

based on both pathological examination of

the surgically removed tumor and appropriate

immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where

available).

• Review the pathology report of the resected tumour

to assess size and mitotic index along with tumour

location.

• Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant

biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there

is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

• Consult your medical adviser where you have any

doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your

policy has been satisfied.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumour a GIST?

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%), epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than 90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to two- thirds of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately 10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3), respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication challenging. The majority of GIST tumours were previously thought to be benign due to their characteristically bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as “benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as benign or borderline. There is some debate that non- gastric GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5 cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site, that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields (mitotic index)

Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

Check their company’s critical illness definition to ensure GISTs are not excluded.

Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was based on both pathological examination of the surgically removed tumor and appropriate immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where available).

Review the pathology report of the resected tumour to assess size and mitotic index along with tumour location.

Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

Consult your medical adviser where you have any doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your policy has been satisfied. G CV

References

1. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Human Pathology 2002 May;33(5):459-65 and Int J Surg Pathol. 2002 Apr;10(2):81-9.

2. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, Hsiung CY, Lu D. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007 Jun;141(6):748-56.

3. Jung ES, Kang YK, Cho MY, Kim JM, Lee WA, Lee HE, Park S, Sohn JH, Jin SY. Update on the proposal for creating a guideline for cancer registration of the gastrointestinal tumors (I-2). The Korean Journal of Pathology 2012 Oct;46(5):443-53.

4. George D Demetri, MD, Jeffrey Morgan, MD, Chandrajit P Raut, MD, MSc, FACS Epidemiology, classification, clinical presentation, prognostic features, and diagnostic work-up of gastrointestinal mesenchymal neoplasms including GISThttp://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-classification-clinical-presentation-prognostic-features-and-diagnostic-work-up-of- gastrointestinal-mesenchymal-neoplasms-including-gist?source=search_result&search=GIST&selectedTitle=1%7E70

Literature review current through: Dec 2014. This topic last updated: Nov 18, 2014.

Management of a patient presenting with GISTs typically involves a combination of surgical and pharmacologic interventions. Existing consensus-based clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggests, for patients with high-risk GIST, the administration of adjuvant imatinib for at least 36 months. (High-risk GIST is defined as a tumour >5 cm in size with a high mitotic rate [>5 mitoses/50 HPF] or a risk of recurrence that is >50%.) Some data shows imatinib therapy can also benefit if the GIST is 3 cm or larger.

Risk of recurrence is very low if the tumor is less than 2 cm and has a low mitotic rate (less than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs). Gastric GISTs have better prognoses than non-gastric GISTs. The cumulative 5-year disease- specific survival rates for GISTs classified at risk levels I, II, III, and IV were 100%, 96%, 67%, and 25%, respectively. (GIST survival statistics can be found on the website at http://nomograms.mskcc.org/GastroIntestinal/ GastroIntestinalStromalTumor.aspx.)

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumour

a GIST?

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls

into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%),

epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with

spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate

compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising

in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other

benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy

alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in

the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true

leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be

difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably

or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the

molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of

GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and

immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them

from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were

inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous

collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than

90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of

the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from

other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other

spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another

tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT

mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived

growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to twothirds

of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately

10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene

or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST

malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their

pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and

have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and

metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or

malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3),

respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication

challenging. The majority of GIST tumours were previously

8

G L O B A L C L A I M S V I E W S w w w . r g a r e . c o m

thought to be benign due to their characteristically

bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming

increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have

the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics

state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as

“benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as

benign or borderline. There is some debate that nongastric

GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are

between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would

be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as

malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5

cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be

labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant

tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific

reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following

claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to

consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

• Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

• Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

• Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site,

that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields

(mitotic index).

• Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree

of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or

distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated

with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or

chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

• Check their company’s critical illness definition to

ensure GISTs are not excluded.

• Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was

based on both pathological examination of

the surgically removed tumor and appropriate

immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where

available).

• Review the pathology report of the resected tumour

to assess size and mitotic index along with tumour

location.

• Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant

biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there

is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

• Consult your medical adviser where you have any

doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your

policy has been satisfied.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumour a GIST?

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%), epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than 90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to two- thirds of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately 10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3), respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication challenging. The majority of GIST tumours were previously thought to be benign due to their characteristically bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as “benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as benign or borderline. There is some debate that non- gastric GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5 cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site, that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields (mitotic index)

Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

Check their company’s critical illness definition to ensure GISTs are not excluded.

Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was based on both pathological examination of the surgically removed tumor and appropriate immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where available).

Review the pathology report of the resected tumour to assess size and mitotic index along with tumour location.

Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

Consult your medical adviser where you have any doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your policy has been satisfied. G CV

References

1. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Human Pathology 2002 May;33(5):459-65 and Int J Surg Pathol. 2002 Apr;10(2):81-9.

2. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, Hsiung CY, Lu D. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007 Jun;141(6):748-56.

3. Jung ES, Kang YK, Cho MY, Kim JM, Lee WA, Lee HE, Park S, Sohn JH, Jin SY. Update on the proposal for creating a guideline for cancer registration of the gastrointestinal tumors (I-2). The Korean Journal of Pathology 2012 Oct;46(5):443-53.

4. George D Demetri, MD, Jeffrey Morgan, MD, Chandrajit P Raut, MD, MSc, FACS Epidemiology, classification, clinical presentation, prognostic features, and diagnostic work-up of gastrointestinal mesenchymal neoplasms including GISThttp://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-classification-clinical-presentation-prognostic-features-and-diagnostic-work-up-of- gastrointestinal-mesenchymal-neoplasms-including-gist?source=search_result&search=GIST&selectedTitle=1%7E70

Literature review current through: Dec 2014. This topic last updated: Nov 18, 2014.

Management of a patient presenting with GISTs typically involves a combination of surgical and pharmacologic interventions. Existing consensus-based clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggests, for patients with high-risk GIST, the administration of adjuvant imatinib for at least 36 months. (High-risk GIST is defined as a tumour >5 cm in size with a high mitotic rate [>5 mitoses/50 HPF] or a risk of recurrence that is >50%.) Some data shows imatinib therapy can also benefit if the GIST is 3 cm or larger.

Risk of recurrence is very low if the tumor is less than 2 cm and has a low mitotic rate (less than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs). Gastric GISTs have better prognoses than non-gastric GISTs. The cumulative 5-year disease- specific survival rates for GISTs classified at risk levels I, II, III, and IV were 100%, 96%, 67%, and 25%, respectively. (GIST survival statistics can be found on the website at http://nomograms.mskcc.org/GastroIntestinal/ GastroIntestinalStromalTumor.aspx.)

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 1 — Is the tumor a GIST?

Histologically, the appearance of GISTs usually falls into one of three categories: spindle cell type (70%), epithelioid type (20%) and mixed type (10%). Those with spindle cell GISTs have a slightly better survival rate compared to epithelioid or mixed histology GIST tumours.

The differential diagnosis of a subepithelial tumor arising in the GI tract is broad, including GISTs and other benign and malignant tumours. By light microscopy alone the distinction among GISTs and other tumours in the differential diagnosis (particularly leiomyomas, true leiomyosarcomas, and GI tract schwannomas) can be difficult, because the histologic findings do not reliably or specifically relate to the immunophenotype or the molecular genetics of the lesions. Accurate diagnosis of GIST typically relies on a combination of cytologic and immunohistochemical characteristics to distinguish them from other GI mesenchymal tumors.

By the early 1990s, it became apparent that there were inconsistencies and ambiguities in the heterogeneous collection of tumours classified as GISTs. Greater than 90% of GISTs express the CD117 antigen as evidence of the KIT mutation, which helps distinguish this tumour from other bowel wall tumors such as leiomyomas and other spindle cell tumors (which are CD117 negative). Another tyrosine kinase mutation that is occasionally seen in KIT mutation-negative GIST tumours is the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Also up to two- thirds of GISTs are CD34 immunopositive. Approximately 10% of adult GISTs lack mutations in either the KIT gene or the PDGFRA.

Critical Illness Claims Issue # 2 — Is a GIST malignant?

The biologic behavior of GIST is variable. In terms of their pathology, GISTs invade the stomach or bowel wall and have the potential to spread regionally to lymph nodes and metastasize to distant sites as well.

GIST tumours can be coded as benign, borderline or malignant (ICD-O-3 codes 8936/0, 8936/1, or 8936/3), respectively, making critical illness claims adjudication challenging. The majority of GIST tumors were previously thought to be benign due to their characteristically bland histopathologic features. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs, over time, have the potential to express malignant behavior. Academics state that it is not appropriate to define any GIST as “benign” (although the /0 code is still used clinically).

Most low or very low risk GISTs can be designated as benign or borderline. There is some debate that non- gastric GISTs that are designated as “low risk” and are between 2 cm and 5 cm should be labelled malignant.

GISTs that are classed as intermediate or high risk would be labelled as code /3 and therefore designated as malignant. This would mean that any GIST greater than 5 cm or has greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs would be labelled as malignant.

The RGA view

If a critical illness definition of cancer requires a malignant tumor, and if the cancer definition does not make specific reference to GISTs in the exclusions, then the following claims approach could be justified.

Subject to the underlying definition, we are likely to consider the following as valid CI cancer claims:

- Any gastric GIST > 5 cm in size.

- Any non-gastric GIST > 2 cm in size.

- Any GIST of any size, and originating in any site, that has > 5 mitoses per 50 high-powered fields (mitotic index).

- Any GIST, in any organ, of any size and any degree of mitotic index, if there is nodal involvement, or distant metastases, or if the claimant is treated with biologic therapy such as imatinib (Gleevic) or chemotherapy.

What assessors should do with a CI claim for GIST

- Check their company’s critical illness definition to ensure GISTs are not excluded.

- Ensure the clinical diagnosis of GIST was based on both pathological examination of the surgically removed tumor and appropriate immunohistochemical proof of a GIST (where available).

- Review the pathology report of the resected tumor to assess size and mitotic index along with tumor location.

- Read the clinical notes to determine if adjuvant biologic- or chemotherapy has been used, or if there is evidence of nodal or distant metastases.

- Consult your medical adviser where you have any doubt as to whether the cancer definition in your policy has been satisfied.