The American Psychiatric Association’s long-awaited fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was released in May 2013.

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was released in May 2013.

The idea of shifting from the long-established classifications provided by DSM-IV has left many in the insurance industry feeling insecure: even some senior staff in Australia, New Zealand and North America have only ever known that version. The trepidation has been encouraged by voracious debate over this edition. (Many will recall similarly animated responses to prior revisions.)

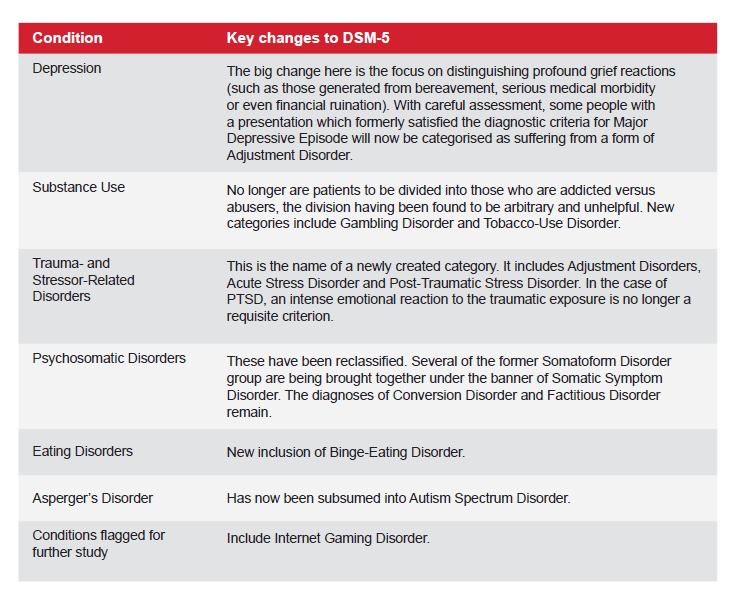

In reality, the revisions and novel inclusions in this new edition are unlikely to make a substantial difference to claims management, yet they highlight the desirability for underwriters to phrase policies with greater specificity, as previously less acknowledged adversities (e.g. binge eating and gambling) were elevated for inclusion in DSM-5.

The DSM is a prominent classificatory system for psychiatric disorders. It is used exclusively in countries such as Australia and the U.S., while professional communities in other countries have elected to work with other systems. For example, Chapter 5 of the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) In Occupational Health is used in the United Kingdom and is reasonably complementary to DSM-5.

A fundamental element in the nature of the DSM, and indeed of all classificatory systems, is that these are all works in progress which are continually under assessment and review. Learned academics are appointed to steering committees, sub-committees and working parties to review current scientific literature with a view toward arriving at a consensus approach to the classification and definition of various disorders. There are always detractors who disagree with the essential opinion of a given working party, but ultimately doctors need diagnostic labels from an operational perspective as an aid to clinical communication and treatment, and to allow them to draw together people of similar clinical presentations for the sake of researching the causes and effective treatments of a given condition.

Yet this need to classify people of similar situations into one group for the purpose of research and treatment is probably at the heart of the greatest criticism of any psychiatric classification, as one’s agreement with a particular diagnosis opens the door towards unhelpful labeling and stigmatization. One expects that, for example, the newly- introduced item of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder has been included to facilitate research into the extreme distress regularly experienced by 3% to 8% of women, and not so as to classify them as suffering a mental illness per se.

While the preambles to these tomes consistently warn that one should not apply such classifications outside of clinical and research contexts, the reality is that our industry requires reproducible and reliable diagnostic criteria by which we can contemplate our approaches to claimants with similarity of presentation and prognosis. While many argue that the DSM fails to provide the reliability and reproducibility we seek, it is the best the American Psychiatric Association has been able to offer after a decade of deliberation.

For the purpose of this overview, it is probably unhelpful to spend much time discussing the many valid criticisms of such classificatory systems in general, and of the DSM specifically. It is, however, important to acknowledge that psychiatry still has no objective strategies for diagnosing mental illness; reliance on the patient’s self-report remaining pivotal. While it remains unclear whether or not this classificatory revision will be allowed a foothold in the marketplace, it is now timely to acquaint ourselves with some of the changes, particularly some of those of significance to our industry.

Clinicians with whom you liaise will continue to cause confusion, primarily because real patients don’t often fit readily into some number of clearly defined diagnostic boxes. There will be a period of exacerbated anxiety over the labeling of a presentation while we all bring ourselves to speak the same diagnostic language, even though in most instances DSM-5’s changes will have little real impact on the insurance industry. Especially over the next year or so, if we wish to be precise, it will behoove all involved in the use of diagnostic terminology to establish with clarity which precise version of the DSM criteria is being used when applying a particular diagnostic label.

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)