The clinical understanding and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most prevalent adult leukemia in the West, has experienced several advances over the past decade.

Research on genetic aspects of CLL has expanded medical understanding of its risk stratification, uncovered a new precursor condition – high-count monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) and overall elicited a sizable transformation of CLL’s treatment framework. Traditional chemotherapy-based regimens, which cause severe adverse effects in the elderly and in patients with comorbidities, are now being paired with (and in some cases supplanted by) targeted therapies such as the recently developed monoclonal antibody immunotherapy drugs ofatumumab and obinutuzumab and the targeted kinase inhibitors idelalisib and ibrutinib. These drugs are not only filling a major unmet need of those with newly diagnosed or resistant CLL, but also may reduce or even potentially eliminate the need for chemotherapy. Indeed, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) named these new therapy options for CLL the Cancer Advance of the Year in its Clinical Cancer Advances 2015 report.

This article focuses primarily on recent advances in the clinical understanding and treatment of CLL and prognostic implications for insurers.

Background

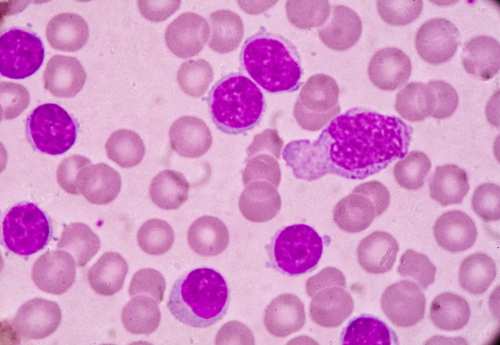

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a slow-developing cancer that is characterized clinically by the overproduction and accumulation of small mature-appearing (but functionally incompetent) B lymphocytes in blood, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues.¹

CLL is the most common adult leukemia in Western societies, with an incidence of 4.2:100,000/year. However, it is relatively rare in Asia3 and Africa. The reason for this geographical diversity is not clear, but the etiopathogenesis is suspected to be more likely due to genetic than environmental factors.4

The risk of developing CLL increases progressively with age. Nearly 70% of patients are 65 years of age or older, and its risk is 2.8 times higher for men than for women.²

Diagnosis

CLL was once thought to be a homogenous static disease, in which B lymphocytes accumulated largely due to lack of normal cell death. Recent research, however, has established CLL as a heterogeneous disease exhibiting constant turnover of malignant B lymphocytes at varying rates. This heterogeneity translates into varying clinical courses and responses to treatment.5,6

More than 80% of CLL patients are diagnosed incidentally. Ten percent of CLL patients present with the characteristic symptoms of fever and night sweats, and approximately 20% to 50% present with enlarged and palpable lymph nodes, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. A small percentage also experience unexplained weight loss and frequent infections.

Diagnostic criteria for CLL developed by the National Cancer Institute’s Working Group19,25 includes the following:

- A peripheral blood B lymphocyte count of at least 5 × 109/l (5,000/ul)

- Clonality of the circulating B lymphocytes should be confirmed by flow cytometry

- The presence of atypical lymphocytes, cleaved cells or prolymphocytes should not exceed 55% of peripheral lymphocytes

- The lymphocytes should be monoclonal B lymphocytes, expressing B lymphocyte surface antigens CD19, CD20, and CD23 with low surface immunoglobulin and the T cell antigen CD5

- Each clone of leukemia cells is restricted to expression of either kappa or lambda immunoglobulin light chains

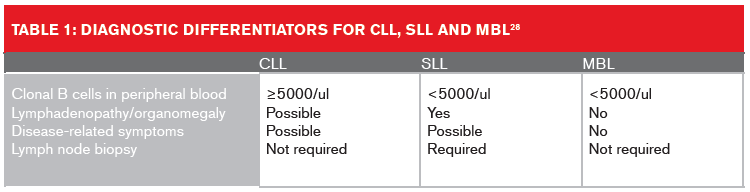

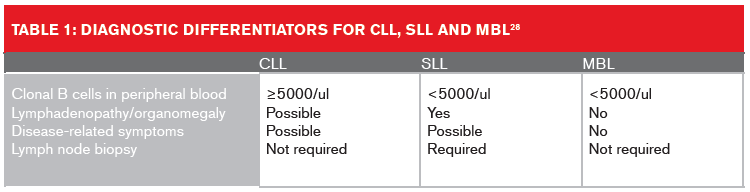

Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is considered the same as CLL by the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematological malignancies due to their identical immunophenotypes. A confirmed diagnosis of SLL requires the presence of lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, and an absolute lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood of less than 5 × 109/l.26

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), which today is recognized as a precursor condition to CLL, was first described in 2005.27 MBL is currently defined as the presence of fewer than 5,000 monoclonal B lymphocytes/μl in the blood in the absence of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or cytopenia. Based on the size of the clone, MBL can be segregated into two groups:

• Clinical or high-count MBL with ≥0.5 × 109/l clonal B cells. This is a preleukemic disorder; progression to CLL occurs in 1% to 2% of MBL cases per year.

• Low-count MBL, with <0.5 ×109/l clonal B cells. This is seen in approximately 5% of the general population, especially among individuals older than age 70. It has little or no apparent clinical significance.

Table 1 (below) lists the diagnostic differentiators for CLL, SLL and MBL

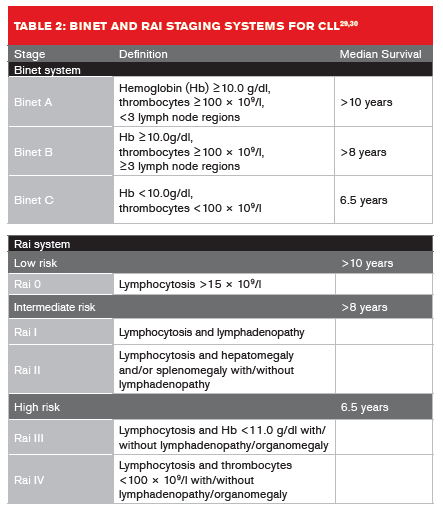

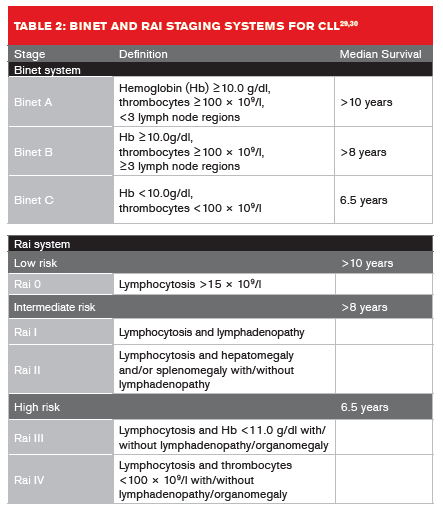

Two clinical staging systems are used to predict CLL median survival rates (Table 2, below).29,30 In Europe, the Binet staging system is more widely used, whereas in the U.S. the Rai system is more commonly applied.

Two clinical staging systems are used to predict CLL median survival rates (Table 2, below).29,30 In Europe, the Binet staging system is more widely used, whereas in the U.S. the Rai system is more commonly applied.

The expanding role of genetic analysis

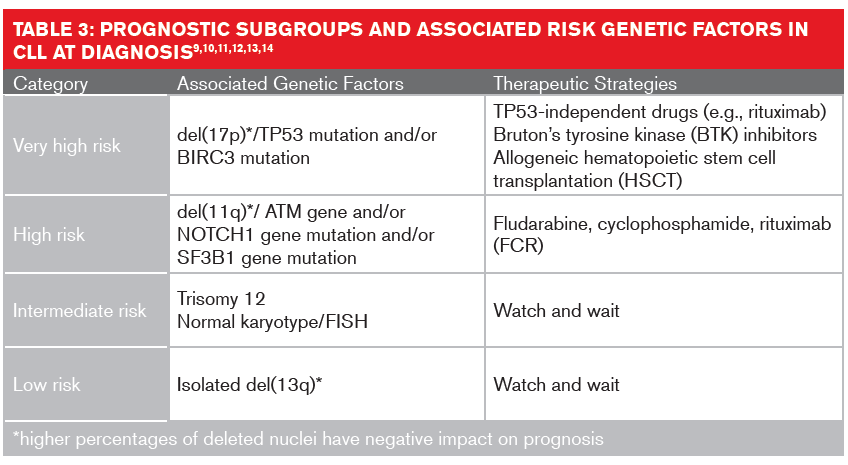

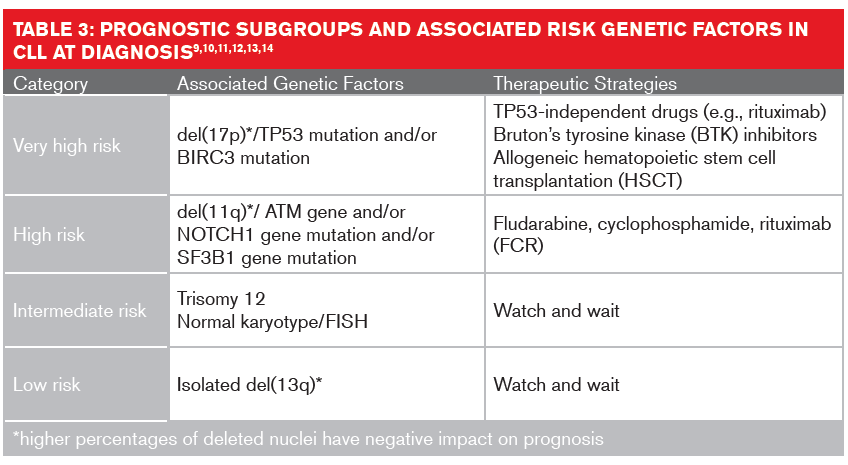

Studies of somatic copy number variations in genomes using karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or single nucleotide polymorphism arrays have identified several genomic mutations that impact the diagnosis, progression and treatment of CLL. The most recurrent diagnostic variations are deletions of chromosome 13q (55% of cases), 17p (7%), 11q (6% to 18%); and trisomy 12 (12% to 16%).7,8

These chromosomal aberrations might not be wholly responsible for CLL’s clinical heterogeneity. Mutations of genes such as IgHV (immunoglobulin heavy chain variable) and the protein coding genes TP53, NOTCH1 and SF3B1 also have implications in prognosis and treatment interventions.9 The mutation status for IgHV19 is generally detected using molecular analysis. About 50% of CLL patients present with unmutated IgHV.20,21 These patients have higher genetic instability and higher risk of gaining unfavorable genetic mutations, resulting in shorter overall survival rates.

FISH analysis is usually performed to detect if the long arm of chromosome 17p, where the TP53 gene resides, has been deleted.16 Patients with a detectable del(17p) mutation or deleted TP53 have the poorest prognoses, with a median overall survival of two to five years.17,18 An extended FISH analysis can also detect additional cytogenetic abnormalities, such as del(11q) or trisomy 12, both of which may have therapeutic consequences. The formerly poor prognosis of patients with del(11q) has improved with the chemotherapy cocktail FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab).19

Clonal evolution refers to the process whereby cancer cells acc umulate genetic and epigenetic changes over time, giving rise to new subclones. In CLL, the heterogeneous nature of the disease likely fuels clonal evolution, which is a key point in its progression, relapse, and chemotherapy resistance:22 Over time, 25% of CLL patients develop a new genetic abnormality in coding or non-coding genes.9Across studies, genetic lesions dominating at relapse have been consistently detected in smaller subclones at earlier stages, suggesting the emergence of fitter subclones together with genetic diversification.23 The most consistent lesions detected in these studies have been preexisting TP53 mutations, resulting in highly genomically complex clones at relapse.16 Chemotherapy exposure has also been shown to result in clonal e volution by inducing de novo mutations conferring major fitness of the related subclones.24

Treatment

There is currently no evidence that early, risk factor-guided intervention with chemoimmunotherapy can alter the natural course of early-st age CLL.4 “Watch and wait,” therefore, remains the standard first-line care for patients with early-stage asymptomatic CLL.

For active symptomatic CLL, the International Workshop on CLL (IWCLL) has specified the following criteria for treatment:31

- Unintentional weight loss of 10% or more within the previous six months

- Significant fatigue

- Fevers higher than 100.5F (38.0C) for two or more weeks without other evidence of infection

- Night sweats for more than one month without evidence of infection

- Cytopenia not caused by autoimmune phenomena

- Symptoms or complications from lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly or hepatomegaly

- Lymphocyte doubling time (LDT) of less than six months (only in patients with more than 30,000 lymphocytes/l [30 × 109/l])

- Autoimmune anemia and/or thrombocytopenia poorly responsive to conventional

therapy

The presence in the genome of del(17p) or of a TP53 mutation without the above mentioned conditions are not indications for treatment.

Whether to administer chemoimmunotherapy depends on patient age (e.g., >65 to 70), fitness level score of >6 (as measured by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale [CIRS]) and renal function (e.g., creatinine clearance <30 to 50 ml/min).32 Front-line treatment of CLL is based mainly on the stage and the specific genetic mutation expressed.

For fit patients (no comorbidities) without the TP53 mutation, the frontline standard of care is chemoimmunotherapy – specifically FCR. This is based on high response rates (40% to 50% complete response), prolongation of median progression-free survival (PFS) and median overall survival compared with administration of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or of chlorambucil alone.33,34,35.36

FCR has its own challenges, as it is associated with significant myelosuppression and infections, making it unsuitable for elderly patients and for patients with comorbidities. For older patients with comorbidities and without the TP53 mutation, regimens can include reducedintensity FCR, chlorambucil + CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab, obinutuzumab, or ofatumumab), or bendamustine + CD20 monoclonal antibody.

For patients with the TP53 mutation, prognosis is generally poor, even after FCR therapy.39 It is therefore recommended that they be treated with the newer inhibitors ibrutinib (which inhibits the enzyme Bruton’s tyrosine kinase [BTK]) and idelalisib (a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor), along with rituximab, in both frontline and relapse settings. For transplant-fit patients responding to treatment with these inhibitor drugs, allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) may also be considered. HSCT is the only modality with documented curative potential in CLL.40

The breakthrough monoclonal antibody immunotherapy drugs obinutuzumab and of atumumab were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2013 and 2009, respectively. The combination of obinutuzumab and chlorambucil was more effective than chlorambucil alone or chlorambucil combined with rituximab, and more than doubled the average time to progression (TTP). The combination of ofatumumab and chlorambucil was also been shown to be superior to single-agent chlorambucil, with an average TTP of 22.4 months versus 13.1 months for chlorambucil alone.38

Newest treatments and therapies

• B-cell receptor (BCR) pathway inhibitors

Currently ibrutinib and idelalisib are approved in the U.S. and Europe for treatment of CLL. Ibrutinib irreversibly inactivates BTK, which is essential for BCR signaling, and nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB), one of the proteins that regulates the expression of genes influencing, among other things, B lymphocyte development and cellular proliferation. Ibrutinib is approved for the treatment of CLL patients who have received at least one round of prior therapy and as the primary therapy for CLL patients presenting with chromosome 17p13.1 deletion.41,42

Acalabrutinib, a second-generation selective BTK inhibitor, has shown promising results for relapsed CLL patients and was recently recommended for orphan drug designation in Europe. It has fewer side effects than ibrutinib, and has shown promise regarding safety and efficacy, including for those with chromosome 17p13.1 deletion.44

Idelalisib is a selective and reversible inhibitor of PI3Kδ, the delta isoform of the enzyme phosphorinositide 3-kinase, which regulates cellular growth and proliferation in leukocytes. In combination with rituximab, idelalisib is a safe and effective new treatment option for patients with relapsed CLL, including those with poor prognostic factors. In a study, patients treated with idelalisib and rituximab lived, on average, 10.7 months without the disease progressing, compared with approximately 5.5 months for participants treated with a placebo plus rituximab.45

• B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) antagonists

BCL-2 is a prosurvival protein which causes apoptosis resistance and accumulation of long-lived clonal lymphocytes in CLL. Venetoclax (ABT-199, RG7601, GDC-0199), a potent BCL-2 inhibitor, has been granted breakthrough designation by FDA for ultra high risk populations with relapsed/refractory del(17p) CLL. A recent study showed that the overall response rate was 79%, the complete response rate 20%, and the 15 month progression-free survival estimate 69%.46

• Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs-T)

Recent clinical studies are investigating the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) modified T cells to treat CLL. CAR-modified T cells have been developed to target antigen CD19 expressed on CLL cells. Treatment of bulky, relapsed, refractory and high-risk CLL with anti-CD19 CAR-modified T cells can result in sustained remissions in small numbers of patients.47

Insurance considerations

CLL is undergoing a rapid and exciting transition right now, from what was, for many, a fatal disease to one that can be controlled for extended periods of time with an array of relatively well-tolerated therapies that to date exhibit very modest long-term risks.

Molecular genetics is changing CLL by offering superior prognostication and treatment strategies. As the understanding of and treatment frameworks for this condition continue to evolve, so are its underwriting risk classifications. Some early-stage favorable cases now exhibit insurable (albeit moderately reduced) life expectancies. Morbidity concerns with CLL, however, still are negatively impacting the ability to consider living benefits coverage.

Promising new therapies for relapsed, refractory and high-risk CLL have shown a remarkable increase in overall survival and progression-free survival, which could impact terminal illness products as the policy terms may no longer be fulfilled.

While developing critical illness products, insurers would be advised to evaluate precursor CLL conditions such as high-count MBL along with early-stage CLL to prevent unanticipated claims, as these conditions may not meet the “serious illness” spirit of the product, given their long life expectancies and the “watch and wait” treatment approach.

Survival in CLL patients over time has improved significantly due to the many new targeted therapies, which are improving not only response rates and progression-free survival, but also overall survival. Additionally, patients who are ineligible for conventional therapies who have relapsed or whose conditions are resistant now have new options, offering the chance of effective treatment. As these trends continue to evolve, insurers will need to watch and track them carefully.

Two clinical staging systems are used to predict CLL median survival rates (Table 2, below).29,30 In Europe, the Binet staging system is more widely used, whereas in the U.S. the Rai system is more commonly applied.

Two clinical staging systems are used to predict CLL median survival rates (Table 2, below).29,30 In Europe, the Binet staging system is more widely used, whereas in the U.S. the Rai system is more commonly applied.